BOW is a Sheffield-based company that writes software to control robots and that software solution can control any robot and extend cover to a wide range of different scenarios.

The company, which was founded back in 2020 as a spin out from Sheffield Robotics, was originally a collaboration between the University of Sheffield and Sheffield Hallam University.

Today it is involved in a variety of projects and recently won two contracts to create robotic systems that will help remove humans from harm on battlefields and assist with the decommissioning of legacy nuclear sites.

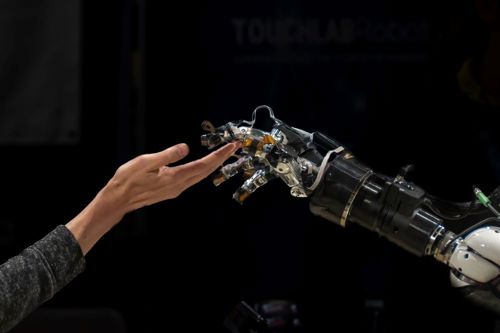

These projects, which were awarded through the Defence & Security Accelerator (DASA) and the Nuclear Decommissioning Authority (NDA), involve “telexistence” technology, which uses cameras, sensors, and other equipment to provide feedback to the system’s operator, so that they feel like they are there in the remote location.

The company’s founder and chief executive is Daniel Camilleri, and he began working on robotics and software while a student at the University of Malta.

“I was studying to be an electrical and electronic engineer and on graduation went to Sheffield University for my Masters, which combined neuroscience with robotics and, to some extent, artificial intelligence. I ended up working on a number of European robotic research projects, focusing on psychology and neuroscience and theories concerning coding, and it was then that I realised there was a real problem when it came to software.

“I’d been working with a specific robot and wanted to switch. I assumed it would be relatively straightforward initially, but it took me over four months to learn how to access the robot’s sensors and to control the body. It required a significant reengineering of the code and while I tried every available solution nothing really allowed me to programme once and then deploy to any robot.”

Camilleri was working at Sheffield University at the time, but while it had a sizeable robotics department he saw few other people using the extensive facilities and he concluded that there were significant amounts of redundant equipment not being used. Why? Because developers were turning to simpler robots, due to the complexities of reprogramming their software.

“It was my ‘eureka’ moment. No one was looking at developing software that could make life easier for developers or that could be easily transferred between robots operating in different environments,” according to Camilleri.

When I asked him why he thought that was the case his response was simple.

“It’s a question I’ve often asked myself. What’s interesting is that no one appeared to be looking at this despite companies and developers throwing resources at robotics. We’ve been able to demonstrate the value of our software and the approach we’ve taken.”

Initial research and the team’s first prototype system, which was based on a new data structure that allowed it to be universal across robots, was focused on a telepresence application which, essentially, allowed users to walk in the shoes of a robot.

“A lot of different people used it, and it generated considerable commercial interest. It was the spark that put us on the road to becoming a spin out from the university,” explained Camilleri.

Robotic attitudes

The spin out was established in March 2020, two years after the idea of universal software was first conceived.

“We set up just as Covid hit – it had been a long process – and it was a challenging time for the business. But while that was the case in many respects the pandemic helped change attitudes towards the use of robotics. People who had been interested, especially in telepresence, and had talked to us about deploying it at some point in the future now saw its benefits and wanted it immediately.”

BOW’s software is focused on removing the barriers to robotics because, at present, individual programmes are created for individual robots that require developers to code a new programme to use the same function on a different robot, or if the robot is upgraded by the manufacturer.

“As I found from my own experience at Sheffield University, robotics development is both time consuming and expensive and this creates a considerable barrier to developments in this space,” explained Camilleri.

“Our software has been described as the ‘Android of robotics’. It’s a single platform that allows different robotic software programmes to be run on every different kind of robot. It’s cloud-based, with low-latency, and is robot-agnostic.”

The company’s technology makes it possible to develop a range of powerful applications for telepresence, which enables the immersive and remote control of any robot, anywhere in the world.

“Applicable to all robots the idea is that the platform is a service that enables users to reduce the learning curve to just a matter of days. It also means that you can decide on which robot to use at the end of a trial period, you’re not tied into any one model. You’re able to trial the software with different robots and then you can make a purchase, which makes the development process much easier.

“Crucially our platform isn’t monolithic. When it comes to developing robotic systems there are a lot of different layers that need to be addressed. Today, if you are developing a robotic application, you must develop everything and then maintain it. With our approach and using our software you can use a more open and modular architecture.”

When the company started it conducted a number of outreach events around the EMEA region.

“We found that almost everyone we met had bought a robot but couldn’t programme it, and so it was gathering dust in the corner somewhere,” said Camilleri. “It was then that we realised we were on to something. Our software made it possible for robots to operate with a single robot arm, or other arms, and could now operate easily with cameras. The opportunities were immense.”

According to Camilleri the company is working closely with a growing number of clients.

“We’re more involved at this stage as we need to better understand how the software is being used, what companies are using it for, so we really understand how it is used before taking a more hands-off approach,” he explained.

The company’s roadmap looks to develop software for telepresence where there is full manual control, but as more data is collected greater autonomy will be possible.

“There’s a lot of IP in the company and obviously we are looking at artificial intelligence. My experience was in psychology and neuroscience so out approach to learning is how we can mimic the way that people learn. However, our approach is different. We want to make the process more transparent to better understand and track the decision-making process. Today, one of the big issues with AI is that it’s like a ‘Black Box’ and people aren’t sure how it reaches a particular decision. We want to better understand what triggers a particular decision.”

Projects

As mentioned, BOW is currently involved with several projects involving the creation of robotic systems that will help remove humans from harm on battlefields and assist with the decommissioning of legacy nuclear sites.

The first project - TEL-MED – involves the company taking and extending its general-purpose software to assess a patient’s injuries in hazardous environments such as a battlefield and to offer first-aid treatment.

The second project - TEL-ND – sees BOW using the same robot but extending the software to address the safety requirements and specialist needs of nuclear decommissioning tasks.

“Both projects involve telexistence technology,” said Camilleri, “and builds on our previous work in developing systems for disposing of explosives and operating robots underwater.”

When a soldier is injured or falls ill on a battlefield, they will be assessed initially by a combat medic technician (CMT), who will have received similar training to a civilian paramedic or ambulance technician. These technicians, however, can be put at risk so Dstl – which is backing the research - wants to be able to identify a patient, report observations of any injuries, and relay pictures and videos to a remote operator.

“The medical system that they want to develop will be able to monitor a patient’s pulse, their breathing, skin temperature, and will be able to attach a blood pressure cuff and take a sample of blood as well as take down the person’s medical history,” explained Camilleri.

“It will need to be able to operate over an extended period of time and we are working with other companies to deliver a system that will push existing technical limits from haptics to improved visual feedback enabling the operator and robot to work together.”

Other companies involved in the different projects include Touchlab, an Edinburgh-based firm that has created touch-sensitive artificial “skin” for robots to feedback information to their operators; three-dimensional (3D) vision technology developer i3D Robotics; and the Nuclear Advanced Manufacturing Research Centre (NAMRC) at the University of Sheffield.

“The vision aspect of the TEL-MED project has been interesting. We’ve implemented a stereo, 180-degree camera with a high frame rate that will ensure high situational awareness. There’s two-way audio and importantly the project is looking to create a level of responsiveness that mirrors the mannerisms of the operator so that the victim is made aware that there’s a human operator handling the robot.”

Once the assessment has been completed human medics would then be despatched, according to Camilleri.

“There’s also research being undertaken into deploying autonomous flying vehicles that would be flown into the location to pick up the casualty, meaning that medics won’t be exposed to hazardous or contaminated areas.

“Both projects, this and the work we are doing in terms of nuclear plant decommissioning, allow skilled human operators to carry out important tasks but without putting themselves in danger.

“We are taking human expertise and transporting it into a robot in real time to make the experience safer for people. Our software can control many different types of hardware, which means we can use off-the-shelf components for these systems, making them easier to replace and keeping costs down.”

The software that BOW has developed also has applications across society, and could help provide improved remote healthcare, support the travel and conference sector, and make it possible for people to work in a variety of dangerous environments.

“We’re opening the doors to a host of new and innovative robotic services,” said Camilleri.

“Our aim is to help develop new applications across more sectors – whether in business, in the home or in social care.”