This is the aim of Electricity: The spark of life, an exhibition which will open at London’s Wellcome Collection on 22 February 2017. According to the Collection, the exhibition aims to trace mankind’s quest to understand, unlock and master the power of electricity.

Three museums are collaborating to organise and host the exhibition. Wellcome, which will be the exhibition’s first host, is contributing artefacts from its collection of electric appliances, particularly medical; Teylers museum in Haarlem, the Netherlands, will be the next, with its collection of early electrical instruments; and finally, Manchester’s Museum of Science and Industry is mainly donating objects relating to the electricity supply industry.

“Our lives today are reliant on electricity on a day to day basis and our consumption in the west is on the increase, so our aim is to bring that to people’s attention and make them stop and reflect about their relationship to electricity,” said Ruth Garde, curator at the Wellcome Collection.

“The idea was initiated by the Wellcome Collection,” commented Dr Alice Cliff, curator of science and technology at the Museum of Science and Industry in Manchester. “It snowballed from thinking about electricity in relation to the body to thinking about electricity as it influences us as a body of people and the title reflects the fact that it is an incredible force and influence in our lives.”

The exhibition is organised into three core themes – generation, supply and consumption.

“The exhibition is largely chronological,” Cliff explained. “The first section ‘Generation: The Great Invisible’ looks at early experimentation with electricity, and the instruments and apparatus that were used in the 18th and 19th centuries to understand the phenomenon.

“The section on ‘Supply: Wiring the World’ focuses on how we’ve harnessed the power and force of electricity. So it looks at how supply began, from the experimental harnessing of energy to large scale supplies to homes and businesses.

“The third section, ‘Consumption: the silent servant’, is about how we use electricity. It looks at how we now take for granted our ability to use electricity in our daily lives. So it features some typical appliances and highlights the ways we use electricity and how that has impacted us.”

More specifically, the third section will consider our energy dependence and power cut issues; experiences of living ‘off the grid’ and more sustainable means of generating electricity.

Each of the themed areas features a piece of contemporary art which reacts to and is in conversation with the historical materials in each space.

Irish artist John Gerrard was inspired by Galvani’s scientific instruments to create a digital environment. This will be shown in the generation section, alongside one of Galvani’s books detailing his bioelectrical experiments and other early devices designed to generate an electric charge, inspired by natural phenomena, such as electric fish and lightning.

One of the instruments that will be on display is a discharge, or aurora, globe (pictured left). The globe was first made in 1789 by English instrument maker John Cuthbertson to demonstrate the effect of rarefied gas on a spark of fire.

The globe, which contains a partial vacuum, can be connected to an electrostatic generator that generates static electricity by friction. As soon as an electric discharge takes place, bands of light are formed in the globe – emulating the Aurora Borealis – which generates light.

In the supply section, filmmaker Bill Morrison explored early film footage from the Electricity Council to create a work that considers the expanding electricity network in the landscape. It will be shown alongside early devices which harness, convert and store electricity, including a voltaic pile and a Barlow’s wheel, as well as photographs featuring pylon designs and other artefacts embodying the challenge in setting up an electric network.

The Barlow’s wheel (pictured right), built by English mathematician Peter Barlow in 1822, was an early kind of electric motor which combined electricity and magnetism to produce continuous motion.

For it to work, an electric circuit is created using a wet battery; the current then passes through a metal wheel – usually made of copper – and continues through a trough of mercury located below it. A horseshoe magnet is positioned around the wheel which provides a magnetic field. The interaction of the current with the magnetic field causes the wheel to rotate.

In this case, a spike wheel is used instead of a solid round wheel. Although the circuit is broken when a tip of the serrated wheel leaves the mercury, the wheel has enough momentum to keep turning until the next tip dips into the mercury, which re-establishes the connection.

The Barlow’s wheel was one of the first machines to harness the interplay between electric and magnetic forces that had been discovered just two years earlier by Hans Christian Ørsted.

Visitors will also see two sections of the mains electricity cable from 1889 and 1890. According to the Museum of Science and Industry, this was the first high voltage cable, and the examples shown in the exhibition use waxed paper as insulation, rather than rubber. Waxed paper was found to be cheaper and more effective – important, given that four seven-mile mains were to be laid across the city.

In the consumption section, French artist Camille Henrot will set up a motorised zoetrope which questions the relationship between human, technology and the environment. A zoetrope, invented in 1834, was an early form of motion picture projector that consisted of a drum containing a set of still images that was spun to create the illusion of motion. It would originally have been hand cranked.

This piece will be surrounded by a range of objects, including examples of neon lighting and light bulbs; applications in healthcare, in areas such as electrotherapy and X-ray technology; an audio installation; and a model of the ‘Smart City’ project, Masdar City.

Initiated in 2006, Masdar city, located 17km outside of Abu Dhabi in the United Arab Emirates, relies on solar energy and other renewable energy sources.

An object worth highlighting in this section is the Archer electric kettle, created in 1902. This was one of the first kettles to have a boil-safe device. The element was sealed in the base of the kettle, and had a fusible cut out – like an electric fuse, the circuit was broken by the melting of a metal alloy.

“The aim of the exhibition is also to show how enmeshed electricity is into our cultural life and how deeply it has permeated our culture, arts and literature,” Garde said. “Which is why we are showing cultural artefacts such as books, art and photography.”

When asked what objects she thinks stand out, Garde answered: “Galvani’s book is quite wonderful – it is the original from 1792 – and the early voltaic pile is so important to the history of the understanding of electricity.

“It was created in 1799 by Italian scientist Alessandro Volta and it was the first electrical battery. It consisted of 49 pairs of copper and zinc plates, separated by pieces of cloth drenched in saline or acid. Volta’s pile demonstrated for the first time that electricity could be generated chemically and would flow steadily, like a current of water, instead of discharging itself in a single spark or shock.”

Cliff and Jan Hicks, archives and information manager respectively at the Museum of Science and Industry, said they chose the original chisel and section of cable with which Sebastian Ziani de Ferranti conducted the chisel test in 1890.

“New Electronics’ readers are probably very familiar with Ferranti’s products, but they might not be so familiar with his early entrepreneurship,” Cliff commented.

Ferranti was a bit of a genius, starting his first job at Siemens at the age of 17 and setting up his own company a year later, in 1882, with a friend of his father’s, Alfred Thompson, to produce an alternator with a zigzag armature.

“Ferranti was very much about alternating current, which was unusual for the time,” Hicks explained. “Most of the research work done by the American inventor Thomas Edison was in direct current, which was seen as being much safer.”

Ferranti then started to work with the Grosvenor Gallery Supply Company, set up by Sir Coutts Lindsay; firstly, to supply his art gallery and then Grosvenor Place with electric lighting. By comparing his own design of AC generators with those of the gallery, Ferranti greatly improved their efficiency and voltage capacity, which led to the foundation of the London Electric Supply Company, of which he was chief engineer in 1887.

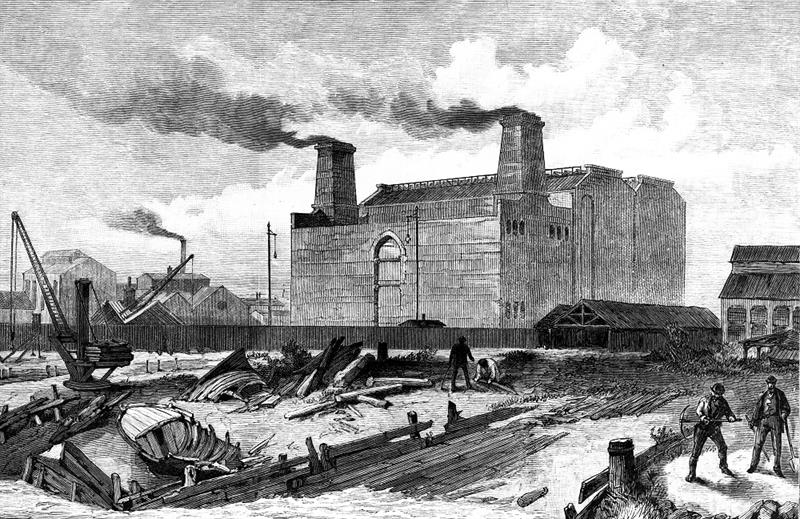

In 1890, at the age of 26, Ferranti became responsible for designing the buildings, the generator supplies and the distribution system of Deptford Power Station – said to be the largest in Europe at the time.

“At that stage, there was something called ‘the battle of the systems’,” Hicks said. “The battle between DC and AC current.”

Ferranti wanted to supply 10,000V from the Deptford power station (pictured right) to substations closer to consumers, but this was something that had never been done before and cables did not exist for that voltage. AC current was seen as unsafe compared to DC current; Edison had conducted a public test on an elephant with AC current which had killed it. In his mind, this proved beyond doubt that it was unsafe.

Ferranti decided to design his own cable. It contained, within the same casing, both the conductor for the out current and the return current. It consisted of two copper tubes, one within the other, separated by an insulating substance consisting of layers of chemically pure brown paper, saturated with melted earth wax. Outside the outer tube was another layer of the insulating substance and the whole was inserted into a protecting tube of iron.

An agreement was reached with three railway companies to lay the mains on the surface along railway tracks and across the bridges to the Charing Cross, Cannon Street and Blackfriars stations. A similar agreement with the Metropolitan and District Underground Railway was reached to use the rail tunnels.

The Board of Trade was sceptical about whether Ferranti had provided an effective means of earthing a 10,000V current in the event of mishap.

Ferranti decided he would also do a public demonstration to show that it was safe (left). He had a section of cable laid out in the yard at the Deptford station and while a supervisor held a chisel to the cable, a foreman struck the chisel with a sledgehammer, which broke the cable. This broke the current, as the current was fused and the cable was earthed. No one was hurt, which therefore proved his point.

“He was a showman, like Edison,” Cliff claimed. “He was our British showman for AC electricity.”

Garde hopes all these exhibits leave visitors with a renewed sense of wonder about the magic of electricity. “I am now much more aware of the ubiquity and importance of electricity in our lives and the issues involved, and I hope visitors will be too.”