Less than an hour by train from London, Cambridge has its University and is at the heart of the high-technology Silicon Fen. It’s also home to a number of notable museums, some of which are run by the University of Cambridge Museums consortium while others are independent of it.

Among the latter group is the Centre for Computing History, a little gem of a museum that can be found on a small industrial estate, just outside the centre of the city.

The Centre was established as an educational charity to tell the story of the ‘Information Age’ through exploring and better understanding the historical, social and cultural impact of developments in personal computing. Crucially, it looks to provide ‘inspirational learning opportunities’ for a wide range of audiences, from primary schools to university students, offering programming and electronics workshops.

It also delivers training sessions to teachers to give them the knowledge, skills and importantly, the confidence, to teach computing to their students in an engaging way.

Jason Fitzpatrick is the founder and CEO of the museum and when New Electronics met with him, over the summer, he was celebrating the news that the museum had just received funding, worth £1million, from one of Arm’s founders and its CTO Mike Muller.

CEO and founder, Jason Fitzpatrick

“This is great news for the museum and will enable us to purchase the Cambridge premises. It means we now have a permanent home for the over 38,000 historically significant artefacts we have here.

“It’s transformative and will provide long term security for the collection. It will allow us to concentrate on developing what we can offer to visitors and students, and helps us to develop our education programme,” Fitzpatrick explained.

Commenting on his decision to support the museum Muller said, “I have been involved with the Centre for years, and am consistently impressed by how imaginative and ambitious the team is in their mission to tell the story of one of the world’s most important inventions - the computer.

“I hope that this investment will help the museum to continue on its trajectory and urge others in the industry to support it – the preservation of this history plays a key role in inspiring the next generation of tech talent.”

The Centre moved to its current site in 2013 and as an idea came about because Fitzpatrick believed that there was a need to tell the story about the impact of computers on society and politics.

“I’d always been interested in collecting computers and hoarding parts. I started buying a few items and over time widened the pool to include other forms of computing devices. I’d always had a passion for computing and was intrigued by the industry and its development.

“What encouraged me to start the collection and ultimately create the museum, was that I realised that people had a real interest in the technology.

“People cared about their computers and remembered playing computer games for the first time, or when they first got to use a personal computer or used it to write a university thesis. This collection comes from a time when the stories about computing were more about the people who used them, and less about the machines themselves.

“The 1980s saw a generation of tech savvy users emerge who went on to create a fantastic industry here in the UK- it was essentially an industry built in people’s bedrooms and we’ll never see the likes of that again.”

The original collection was housed at Fitzpatrick’s place of work – he was a web developer - and it was only in 2013 that he decided, with the help of colleagues and friends he’d met and worked with over the years – including Mike Muller – to set the museum up in its current location.

“People said they’d be interested in a museum that looked to preserve technology and ensure that it was valued, celebrated and secured for posterity,” he explained.

A significant collection

The Centre for Computing History has an internationally significant collection of vintage computers, memorabilia, artefacts, documents and hands-on displays.

“It includes 1119 historic computers as well as 247 games consoles along with peripherals, video games, software packages, books, manuals and magazines and we are continually adding to the collection,” said Fitzpatrick.

The video game designer David Jones, for example, donated his Tandy TRS-80 Model III computer to the museum.

“It was the machine that he used to create his classic games featuring ‘Magic Knight’, Finders Keepers and its sequels, which were released on cassette for home computers including the ZX Spectrum, Amstrad, and Commodore 64.

“David also donated a host of floppy disks and a 15 megabyte hard disk that contained the original source code and assets for many of his games,” Fitzpatrick explained.

The collection is certainly vast but when pushed Fitzpatrick points out three particularly important exhibits.

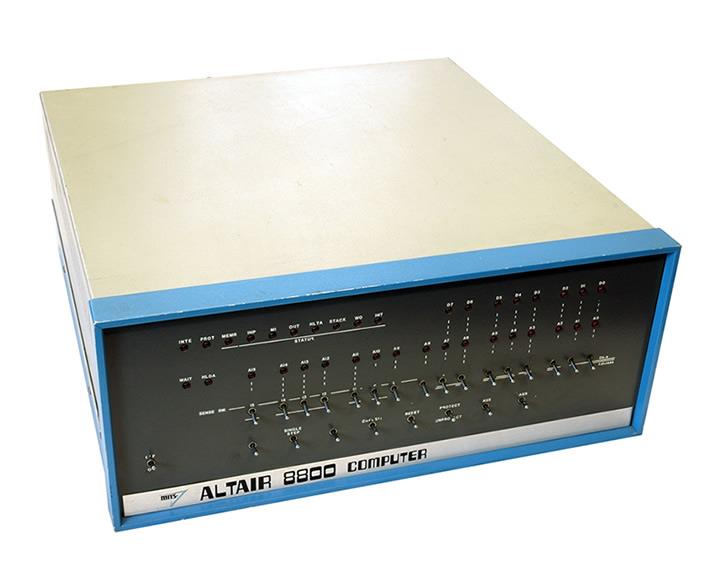

“The first is the Altair 8800, which is commonly referred to as the world’s first personal computer. While that can be debated, its claim to fame is primarily the impact it had on two strands of computing. Firstly, on seeing it Bill Gates thought he would be able to write software for it and Microsoft was born; while when Steve Jobs used it he was encouraged to develop the first Apple computer. I’d argue that it was pivotal in the development of the computing industry that we have today.”

The Altair 8800 computer

The Altair 8800 sold in huge numbers. It had no screen or keyboard, data had to be toggled in, and it was programmed and answers were received in binary. But despite all that it inspired a generation.

Another key object in the collection is the LEO, which is described as the world’s first business computer.

“The museum and the LEO Computers Society have been awarded a £100,000 development grant from the Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF) to bring together, preserve, archive and digitise a range of LEO Computers artefacts, documents and personal memories.”

LEO appeared in the 1940s and was the result of a decision by J. Lyons & Co.’s, the country’s largest caterer at the time, to invest in the computer developments being made at the University of Cambridge.

“From this collaboration LEO (Lyons Electronic Office) appeared and went on to revolutionise how businesses were run. It is now acknowledged as the world’s first business computer,” said Fitzpatrick.

The preservation of LEO is important and reflects the museum’s ambition to preserve the rich history of computing for future generations.

According to Fitzpatrick, “We recognised the importance of the giant ‘electronic brains’ of the early days of computing as a result of a successful LEO Computers exhibition held in 2017.

“Following that exhibition we realised how much important documentation the LEO Computers Society had and we resolved to make sure the archive was protected for the long term.

“The funding will help to raise public awareness and pride in this important and uniquely British heritage.”

The funding will be used to train staff who will learn practical heritage skills to preserve and digitise LEO material which will then be made freely available via digital archives, wide-ranging learning resources, events and a film, while also exploring the recreation of the first LEO machine using cutting-edge virtual reality technology.

The final key exhibit identified by Fitzpatrick is the Sinclair ZX Spectrum prototype, the “absolute original build of the Sinclair Spectrum that dates back to 1981/2 and which became the first games console.”

The prototype machine has a full travel keyboard with the commands hand written on the top and all the chips are labelled – the underside of the board is all hand wrap wiring.

Accrediation

A significant development for the Centre has been the awarding of ‘Full Accreditation’ status by the UK Arts Council, which sets out nationally-agreed standards, which in turn helps to inspire confidence in the museum not only with the public but with other funding and governing bodies.

“That accreditation was culmination of 3 years of hard work in implementing documented cataloguing systems, preservation processes, development plans and working procedures, demonstrating that the organisation works to a high standard both in our preservation efforts and as a visitor attraction,” Fitzpatrick explained.

“Our vision for the museum was for it to be completely hands on and interactive, and at that time, to my knowledge, there were no other museums with the same ambition. A computer consists of hardware and software, and the only way to experience the software is to physically use the hardware. So to me, a museum with working and usable exhibits was the only way.”

That approach raised the suggestion that the museum was not focused on preserving the artefacts properly.

“Nothing could have been further from the truth,” retorted Fitzpatrick. “An essential and on-going developing area of the museum’s work is the understanding of the chemical make-up of component materials used in computers. Plastics break down relatively quickly, sometimes seen as ‘yellowing’, over time. There is also the interaction of different types of plastics when in contact with each other. Known as ‘cable burn’, certain PVC sleeved cables will, under the right condition, ‘melt’ the ABS plastic that it is in contact with. At the same time some plastics will generate harmful gasses that can negatively affect other materials.

“Another problem area is batteries. Many vintage computers have internal batteries that store configuration information. Some will ‘leak’ over time causing harmful acids to damage the surround electronic circuits, so the museum is making a concerted effort to remove them and protect the machine from potential harm.

“The accreditation highlights our work in maintaining the collection to a high standard and will help us to get the funding we need from the various pots of money that are available including a full National Lottery grant.”

Education

One of the most important aspects of the museum is its engagement with schools via group visits and its outreach programme.

“We’ve had over 104 schools visit the museum in the past year,” said Kirkpatrick, but the Centre is also heavily involved in an outreach programme that brings the museum and parts of its collection to the schools themselves.

“We are able to bring a mini-version of the museum to them!”

According to Muller one of the key reasons behind his decision to provide the £1million funding boost to the Centre was its commitment, through its displays and activities, to support the teaching of computing.

“The team behind the museum is full of passion and commitment and it’s great to be here when it’s full of kids learning.

“It’s a unique facility with a huge collection of artefacts which are supported by demonstrations and a broad range of activities.

“In the foyer there’s the Megaprocessor, which is a computer processor made very large that helps explain what a computer is and does. But once kids have had a chance to look at the collection they can then join a workshop and find out how to program a Raspberry Pi to control a device.

“If we can broaden students’ experience and motivate them to develop new skills and develop an interest in computing, then I think it’s a job well done.

“I put that money into the centre because I want it to thrive and it brings a degree of stability which will enable the museum to focus on the exhibits and on developing its educational programme.”

With its long-term future secured the Centre for Computing History is able to provide visitors with a wonderful opportunity to better understand the impact of computing in a rapidly changing world.