According to the United Nations, some 70% of the global population is expected to be living in cities by 2050. This will mean that large population concentrations will have to be provided with a broad range of stable and sustainable public services which, in turn, will have to be delivered in a safe environment.

Another striking figure is that more than 60% of the world’s economic growth in the next 10 years is expected to come from city areas.

Cities are having to address these pressures in a sustainable and economic way and this has given rise to the concept of the ‘Smart City’ or, perhaps more accurately, the City of Things.

The Smart City is focused on delivering better use of resources, making transport systems smarter and providing more efficient and effective water, waste management, heating and lighting services.

Increasingly, however, rather than a ‘top down’ governmental approach, many of the cities that are embracing the ‘Smart City’ concept do so by taking a radical ‘bottom up’ approach to the development of new, innovative services that, in turn, bring government, citizens, academia and industry together.

In Antwerp, this approach is described by Professor Steven Latré, an assistant professor at the University of Antwerp and iMinds in Belgium, as ‘the quadruple helix’ that is intended to ‘combine and safeguard public interests while at the same time facilitating and supporting creativity’.

“We want people, through the intelligent use of Internet-based communications and applications, to have far more control over their lives,” he says.

Hundreds of smart sensors and wireless gateways have been deployed across the city to create what is in effect a ‘living laboratory’ for the IoT.

“Our aim is to connect citizens across the city with solutions that will improve their quality of life,” he explains. “We’ve turned Antwerp into a large testbed where data will be collected and analysed on a large scale. We’ve created a real life testing environment, rather than use the constrained and controlled environment of a more traditional research environment.”

Singapore is another city looking to become an international guinea pig for smart technologies.

Commenting, Professor Low Teck Seng, CEO of the National Research Foundation (NRF), the national research funding body said: “We are trying to virtualise the whole city and looking to build 3D models of each building, including glass, cement and the internal geography of the building. We are looking to integrate live data from cameras in order to use it for traffic or disaster management.”

In the UK, more than 30 cities either have what can be described as smart initiatives taking place or are looking to roll out such a programme – the landscape is changing rapidly, whether in terms of sustainability, mobility or governance.

One leading city is Bristol, where the ‘Bristol Is Open’ initiative is intended to provide the city with an ambitious research infrastructure to help it better explore developments in software, hardware and telecom networks in order to better promote more machine-to-machine communication.

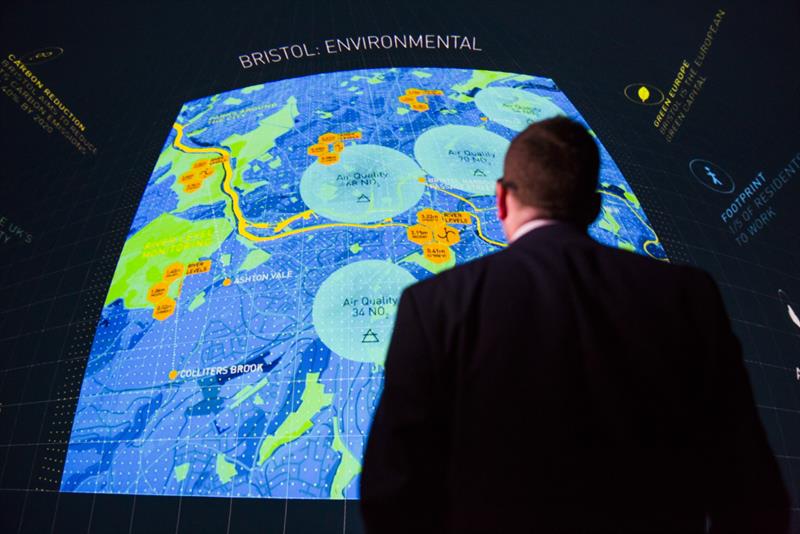

| The Bristol Brain aims to create a 3D-printed large-scale city model on top of which real-time data and sophisticated analytics can be projected and visualised. |

According to Stephen Hilton, Futures Director at Bristol City Council: “We are looking to give people the ability to interact, work and play with the city that they live in. Connectivity is key: most broadband or wireless providers have tended to provide connectivity based on what businesses’ currently need rather than providing additional capacity, where people can gain access to more bandwidth than they need to get started.”

The Bristol is Open initiative is using a high performance software defined network as its operating system. Using the NetOS a growing number of IoT platforms and big data analytics are now in place to support an emerging number of smart city applications.

“Bristol is Open is a joint venture between the city council and the University of Bristol which, since its launch last year, has emerged as one of the UK's largest smart city initiatives,” explains Professor Dimitra Simeonidou, chief technology officer of Bristol is Open. “We are using high performance fibre available for research, as a foundation for new digital services around the city.”

Much like Antwerp, Bristol is determined to turn itself into a ‘high tech testbed for innovation’ and, according to Prof Simeonidou: “We have a 30Gbit/s fibre broadband network powering it.

“Discussions around Bristol is Open started a few years ago. I lead the High Performance Network Group at the university and was focused on open programmable networks, open software and hardware for networking. Prior to Bristol is Open, we had been working on a number of projects around the world looking to open up infrastructures to both technical and vertical market users.

“In Bristol, we are looking to use big data to solve a variety of problems – from air pollution to traffic congestion, as well as assisted living for the elderly.”

“It’s not just about new technology,” suggests Hilton. “People in Bristol are concerned by the quality of air. If we are to improve it, people also need to behave differently and make different choices. We have to be able to connect data to the individual in order to highlight then influence the choices they can make. We need to nudge people towards more sustainable activities.”

The city’s fibre network fibre runs across several miles of council owned BNet ducts and has been upgraded to a 144 fibre core. In addition, the city is deploying a mile of wireless connectivity which, in turn, will be complemented by an RF mesh canopy covering Bristol.

The city’s fibre network fibre runs across several miles of council owned BNet ducts and has been upgraded to a 144 fibre core. In addition, the city is deploying a mile of wireless connectivity which, in turn, will be complemented by an RF mesh canopy covering Bristol.

This is the Brunel Mile, named after the illustrious Victorian engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel, who left a significant physical imprint on Bristol – from the Clifton suspension bridge to the Temple Meads railway station and the Great Western Railway itself.

The Brunel Mile connects the city’s Temple Meads rail station to the SS Great Britain, anchored in the dock area of the Bristol, and provides an experimental test bed for wireless technology such as 5G mobile broadband.

Crucially, in order to manage the mass of data, that is and will be generated by the network of sensors being deployed, the network is being sliced, with each application handed a portion of the available bandwidth.

Canopy of creativity

“In addition to the Brunel Mile, up to 1500 photocells incorporating RF technology will be hosted on street furniture with nine sites used to link the mesh onto the 144 fibre core. This will allow for experimentation and research into machine to machine communications creating an Internet of Things,” explains Prof Simeonidou.

Bristol is Open, which is receiving funding of £75million to cover investment in both infrastructure and technology, involves, as Prof Simeonidou explains, ‘working with communities and software companies to develop applications that will support a wide range of smart city projects’.

As an example, she points to a traffic control application that uses cameras to monitor movements of traffic and people around the city.

“The application which has been developed is able to recognise different types of mobility, including vehicles and groups of pedestrians, and then makes data available for research.”

All these applications are being built on the NetOS, which was developed originally by the university's High Performance Networks research group.

The system is based on software defined networking and network virtualisation principles which, according to Simeonidou, is ‘a first for smart city’.

“We need to be able to tap into the city’s creativity,” Hilton explains, “and the platform that we have created means that smaller companies which are interested in developing applications and services to sit on top of it, will be able to do so.

“Tracking technology is being used by health, education and city transport sectors to monitor and manage the city’s traffic congestion problems and we’re looking at real time transport information that can be transmitted openly, enabling applications to be built around, for example, a family day out to provide better analysis of leisure and retail activity in order to improve services in the future.”

“We have developed an applications store, free for anybody, which at the moment is internal,” explains Prof Simeonidou. “But we will be gradually opening it up for users and to communities for commercial exploitation.”

Crucially, according to Prof Simeonidou: “Our technology is ‘agnostic’, which means that we are able to make all of the applications that have or will be developed more easily transferable into other environments.”

The Bristol Brain

Bristol has also developed an emulator to assist in future developments in the City, but which will also be available to help other smart cities around the world.

“The Bristol Brain,” according to Hilton, “is situated in the city’s 360 spherical planetarium, which was originally a 2000 Millennium project. It’s been retrofitted with 4k projectors, has a fibre link connecting it to a high performance super computer at Bristol University and will be able to project real time data in a 3D environment.

“Open to an audience of 180 people, it will enable them to experience new city scenarios at the same time through 3D visualisation. While we are currently unable to render the city to highest level of detail, we see the data dome as a place where people will not only be able to visualise, but also experience, different models.”

The project is aiming to create a 3D printed large scale city model on top of which real time data and sophisticated analytics can be projected.

“We will be able to show real time pedestrian and traffic flows; the energy use of buildings or the air quality in the city at different times of the day,” enthuses Hilton.

“We want people to be able to leap into the city model, to experience an immersive digital environment that will use virtual reality, augmented reality and haptic technologies to allow people to experience new developments before they are built – meaning that future different scenarios for the city can be explored and their impact on transport, air quality, noise, light and other factors fully understood before any physical development takes place.”

The Bristol Brain could fundamentally change the way the city is planned, enabling citizens and planners to work more closely together to make better decisions

“It will provide a single, holistic planning tool that will be open for all,” says Hilton.

According to Hilton, projects like Bristol is Open are intended to help people to better understand he city they live in and to help cities address some of the biggest challenges of modern urban life. He concludes:

“We need to avoid allowing big business, which will look to standardise technology in order to optimise services, to dominate the smart city concept. A very efficient city is a sterile city and we want to use Bristol is Open as a platform that encourages not only big business, but creatives and innovative start-ups to contribute.”

| Bristol’s Venturer consortium embarks on trials of driverless cars In 2015, the VENTURER consortium was given the ‘green light’ by the then government to explore the feasibility of driverless cars in Bristol.Funded by Innovate UK, the consortium, which is made up of among others Bristol Council, Fusion Processing, AXA insurance and Williams Advanced Engineering, draws on the expertise of a range of organisations from across different sectors to not only look at the technology but assess its impact on the public and investigate both the legal and insurance aspects of driverless cars. “Bristol has a reputation as an innovative city,” says Stephen Hilton, Futures Director at Bristol City Council, “and this project brings together high quality knowledge and developments in digital solutions. The Formula 1 Williams team has put a huge amount of work into developing simulators and the vehicles are themselves being kitted out with virtual technology as we look to test the human aspect when it comes to operating these vehicles.” The VENTURER trial will run for 36 months and testing of the consortium’s autonomous vehicle, the BAE Systems Wildcat, started on both private and public roads in early 2016. “The Wildcat is free range, so it doesn’t need a guided pathway,” explains Hilton. “Bristol is very much a pioneer in the development of this technology. I don’t believe we’ll see a revolution; rather, it’ll be a period of evolution in which autonomous and driven vehicles will have to operate side by side.” According to Hilton, autonomous vehicle technology offers enormous opportunities to influence not only road safety but also issues of particular concern in Bristol, such as congestion, air quality, climate change and social inclusion. “The acquisition of data will be a crucial part of this project,” Hilton suggests. “We’ll be able to look at new insurance models and charging schemes as this marketplace evolves. Our aim is to champion experimental solutions through the deployment of ICT and digital technologies, but by doing so in a people friendly manner.” |