Since then it has developed into an extensive scientific discipline that, in its widest sense, designates diverse techniques for non-invasive visualisation of the internal aspects of the body.

Modern medical imaging systems that utilise fundamentally different physical principles and processing techniques but have one thing in common - an analogue data acquisition front end serving for signal conditioning and conversion of raw imaging data into a digital domain.

This tiny functional front-end block is hidden deep inside a complex machine. However, it is its performance that has a crucial impact on the resulting image quality of the complete system. Its signal chain comprises a sensing element, a low noise amplifier (LNA), a filter, and an analogue-to-digital converter (ADC).

The data converter constitutes possibly one of the most demanding challenges that’s imposed by medical imaging on the electronics design in terms of required dynamic range, resolution, accuracy, linearity, and noise.

So what is required to enable advanced data converters and integrated solutions to work at optimum levels?

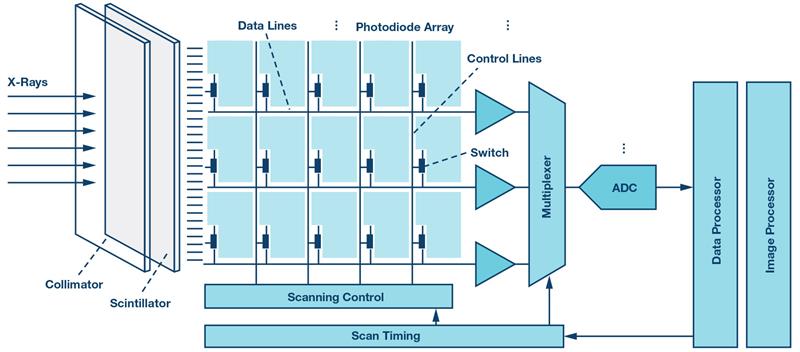

Figure 1: Digital X-ray detector signal chain

Digital radiography

Digital radiography (DR) is based on physical principles common to all conventional absorption-based radiography systems. The X-rays passing through the body are attenuated by tissues of different radiographic opacity and projected on a flat panel detector system, as shown schematically in Figure 1. The detector converts the X-ray photons into electrical charges that are proportional to the energy of the incident particles. The resulting electrical signal is amplified and converted into a digital domain to produce an accurate digital representation of the X-ray image. The quality of this image depends on the signal sampling in the spatial and intensity dimensions.

In the spatial dimension, the minimum sampling rate is defined by the pixel matrix size of the detector and the update rate for real-time fluoroscopy imaging. Flat panel detectors with millions of pixels and typical update rates as high as 25 fps to 30 fps employ channel multiplexing and multiple ADCs with sampling rates up to several dozens of MSPS to meet the minimum conversion time without sacrificing accuracy.

In the intensity dimension, the digital output signal of an ADC represents the integrated amount of X-ray photons absorbed in a given pixel over a specific exposure time. This value is binned into a finite number of discrete levels defined by the bit-depth of an ADC. The signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) is another important parameter that defines the intrinsic ability of the system to faithfully represent the anatomic features of the imaged body. Digital X-ray systems use 14-bit to 18-bit ADCs with SNR levels ranging from 70 dB up to 100 dB depending on the type of the imaging system and its requirements. There are a wide range of discrete ADCs and integrated analogue front ends to enable various types of DR imaging systems with increased dynamic range, finer resolution, higher detection efficiency and lower noise.

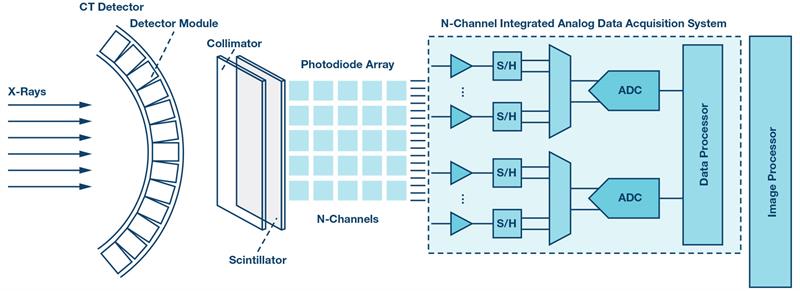

Computed tomography (CT) also uses ionizing radiation but, unlike digital X-ray technology, it is based on an arc-shaped detector system synchronously rotating with an X-ray source and utilises more sophisticated processing techniques to produce high resolution 3D images of blood vessels, soft tissue, and more.

The CT detector is the central component of the entire system architecture and, indeed, is the heart of the CT system. It is comprised of multiple modules, which are depicted in Figure 2. Each module transforms the incident X-rays into electrical signals routed into the multichannel analogue Data acquisition system (ADAS). Each module contains a scintillating crystal array, a photodiode array, and the ADAS, which contains multiple integrator channels that are multiplexed into the ADCs. The ADAS must have very low noise performance to maintain good spatial resolution with reduced X-ray dosage and to achieve high dynamic range performance with extremely low current outputs. To avoid image artifacts and ensure good contrast, the converter front end must have highly linear performance and offer low power operation to relax cooling requirements for the temperature sensitive detector.

Figure 2: CT detector module signal chain

The ADC must have high resolution of at least 24 bits to achieve better and sharper images, and a fast sampling rate to digitise detector readings that can be as short as 100 µs. The ADC sampling rate must also enable multiplexing, which would allow the use of fewer converters as well as the reduction of the size and power of the entire system.

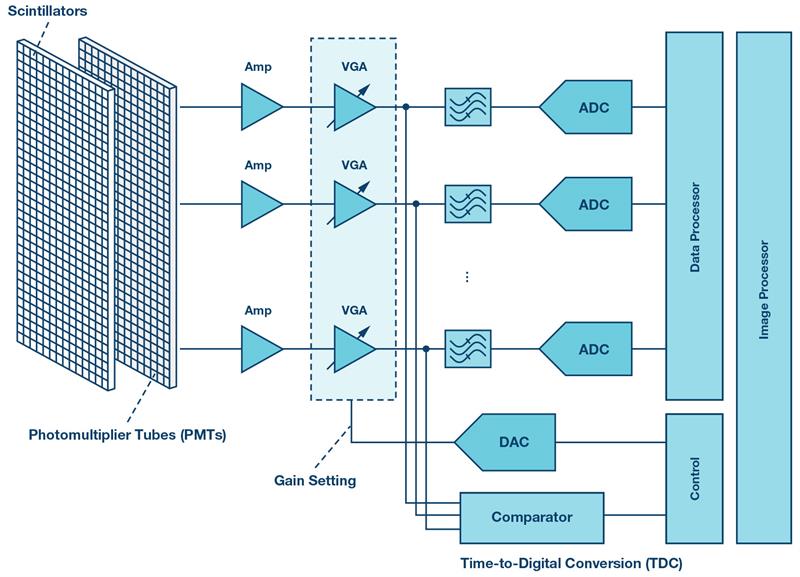

Positron emission tomography (PET) involves ionizing radiation resulting from a radionuclide introduced into a human body. It emits positrons that collide with electrons in tissue, generating pairs of gamma rays radiated roughly in opposite directions. These pairs of high energy photons simultaneously strike opposing PET detectors aligned in a ring around a gantry bore.

The PET detector, schematically shown in Figure 3, consists of an array of scintillators and photomultiplier tubes (PMTs) converting gamma rays into electrical currents that are translated into voltages, and then amplified and compensated for amplitude variations by using variable gain amplifiers (VGAs). The resulting signal is split between ADC and comparator paths to provide energy and timing information used by the PET coincidence processor to reconstruct a 3D image of a radioactive tracer concentration within the body.

Figure 3: PET electronic front end signal chain

Two photons can be classified as relevant if their energies are around 511 keV and if their detection times differ by less than one ten-billionth of a second. The photons’ energy and the detection time difference impose strict requirements on the ADC, which must have good resolution of 10 to 12 bits and fast sampling rates typically better than 40 MSPS. Low noise performance to maximize the dynamic range and low power operation to reduce heat dissipation are also important for PET imaging.

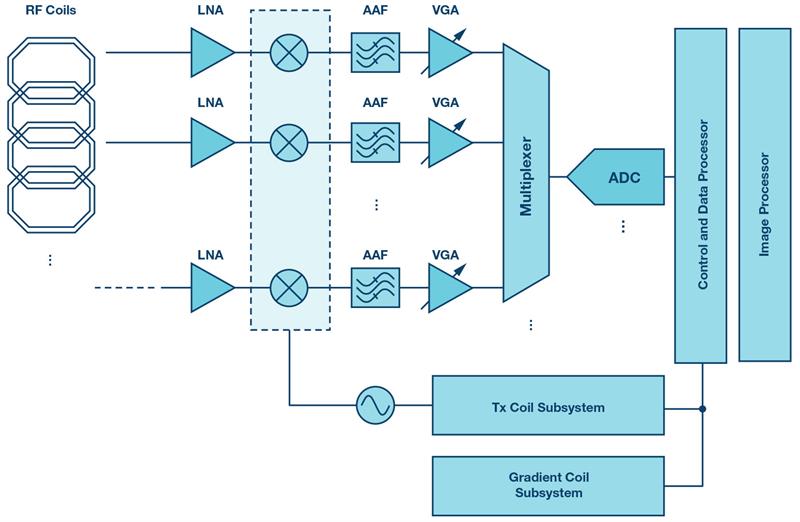

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a non-invasive medical imaging technique that relies on the phenomenon of nuclear magnetic resonance and does not use ionizing radiation, which distinguishes it from DR, CT, and PET systems.

The carrier frequencies of the MR signals scale directly with the main magnetic field strength, with the frequencies ranging in commercial scanners from 12.8 MHz to 298.2 MHz. Signal bandwidth is defined by the field-of-view in the frequency-encoding direction and can vary from a few to several dozens of kHz.

This imposes specific requirements on the receiver front end, which is typically based on a superheterodyne architecture (Figure 4) with lower speed SAR ADCs. However, recent advancements in analogue-to-digital conversion enabled fast and low power multichannel pipeline ADCs for direct digital conversion of the MR signals in the most common frequency ranges at conversion rates exceeding 100 MSPS at a 16-bit depth. The requirement for dynamic range is very demanding - it typically exceeds 100 dB. Enhanced image quality is achieved by oversampling the MR signal, which improves resolution, increases SNR, and eliminates aliasing artifacts in the frequency-encode direction. For fast scan acquisition times, the compressed sensing technique based on under-sampling is applied.

Figure 4: MRI superheterodyne receiver signal chain

Ultrasonography or medical ultrasound is based on a physical principle different from all other imaging modalities discussed in this article. It utilises pulses of acoustic waves in the frequency range from 1 MHz to 18 MHz. These waves screen the internal body tissue and reflect them back as echoes of varying intensity. These echoes are acquired and displayed in real-time as a sonogram that may contain different types of information, including the acoustic impedance, blood flow, motion of tissue over time, or its stiffness.

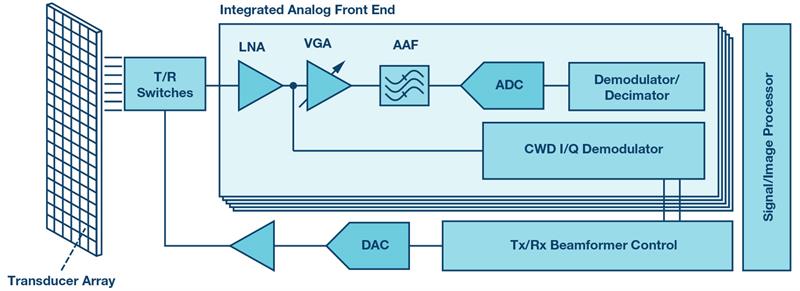

The key functional block of the medical ultrasound front end shown in Figure 5 is represented by an integrated multichannel analogue front end (AFE) that includes a low noise amplifier, a variable-gain amplifier, an antialiasing filter (AAF), an ADC, and demodulators. One of the most important requirements imposed on the AFE is the dynamic range. Depending on the imaging mode, this requirement can demand 70 dB to 160 dB to distinguish between blood signals and background noise resulting from probe and body tissue movements. Therefore, an ADC must provide high resolution, a high sampling rate, and low total harmonic distortion (THD) to maintain dynamic fidelity of the ultrasound signal. Low power dissipation is another important requirement dictated by the high channel density of the ultrasound front end. There are a range of integrated AFEs for medical ultrasound equipment to enable the best image quality, reduced power consumption, and smaller system size and cost.

Figure 5: Medical ultrasound front end signal chain

Medical imaging imposes some of the most demanding requirements on the electronic design. Low power, low noise, high dynamic range, and high-resolution performance at low cost and in a compact package are common trends dictated by the requirements of modern medical imaging systems. To address these challenges companies, like Analog Devices, address these requirements by offering highly integrated solutions for the key signal chain functional blocks so as to enable best-in-class clinical imaging equipment that is fast becoming an integral part of modern healthcare systems.