The research, which covered 330 companies, suggested that many companies would fall foul of new international standards and recently announced plans for a British IoT security law, as well as a proposed Australian code of practice and recommendations from the US Dept of Homeland Security.

Vulnerability reporting enables vendors to be alerted to, and fix, cyber security weaknesses that could be exploited by hackers. It is widely considered to be a baseline requirement of IoT device security. (Scroll down for international regulations and high-profile hacks).

Of the manufacturers that did allow vulnerability reporting, variations exist and many used a weakened policy, with more than a third (38.6%) indicating no timeline of disclosure.

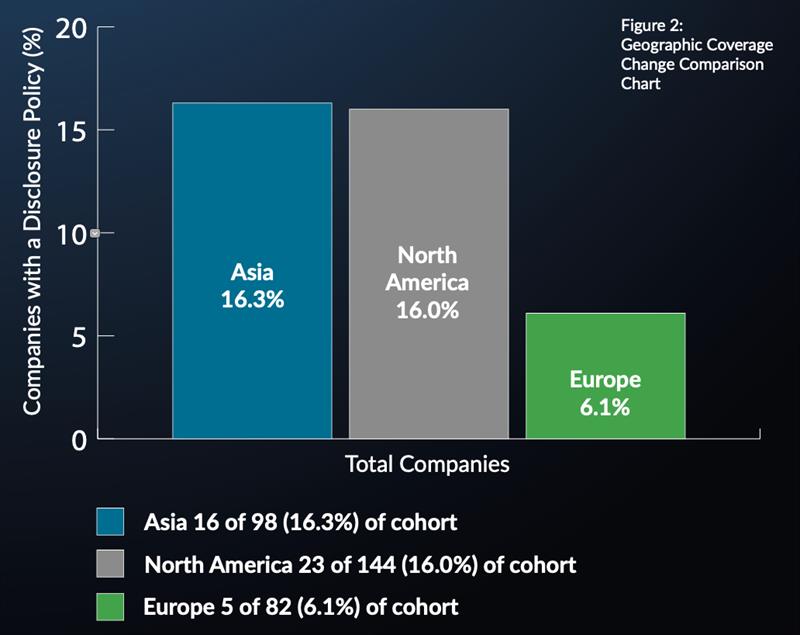

European headquartered firms performed the worst among those questioned. Just 5 of the 82 companies based in the region (6.1%) comply with incoming standards and laws; this compares with 16.0% (23 of 14) of North American firms and 16.3% (16 of 98) of Asian developers.

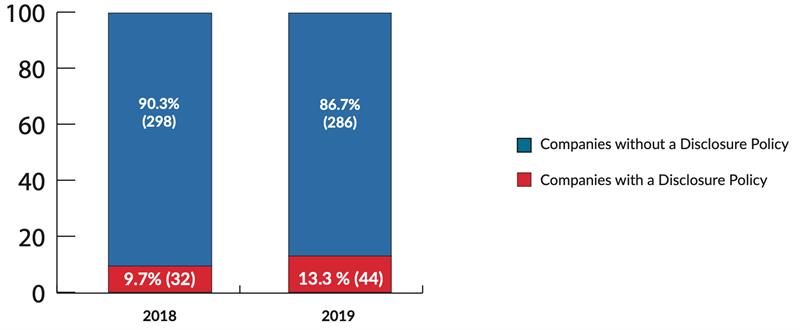

There has been some progress since 2018’s analysis, when less than 10% (32 of 330) implemented vulnerability reporting. The IoTSF report concluded that, “the industry must do better… much better”.

The report shows that, with few exceptions, only major brands supported vulnerability reporting. Those that did included Amazon, Apple, FitBit, Dyson, Garmin, Google, HP, HTC, Huawei, Lenovo, LG, Motorola, Samsung, Siemens, Signify and Sony. A complete list of companies researched, and the results of the study are included in the report.

Of the 44 enabling vulnerability reporting, 18 (40.9%) also included some form of bug bounty, which gives ethical hackers a financial incentive to alert the company rather than trading on the black market. 32 (72.7%) had a secure communication public PGP encryption key; and an additional 9 (20.5%) used a proxy disclosure service.

Earlier this month the UK National Cyber Security Centre (NSBC) advised owners of smart cameras and baby monitors to tweak the settings after buying them. This followed a series of well-publicised breaches.

Commenting on the report, the IoT Security Foundation's managing director John Moor said, “Vulnerability reporting is an essential element for keeping IoT products and services safe from intruders, and is widely considered to be a top 3 operational security measure. For me, it is the number one essential practice that needs to be adopted due to the impact it can have on managing risk exposure.

"The trend for smart connected products continues to grow due to the low cost of the technology and the innovation it unleashes. However, that connectivity brings a risk ‘in the wild’ and it is crucial that security mitigations are managed beyond the design stage and throughout operating life - leveraging the researcher community significantly aids that undertaking.”

While a host of new regulations and laws have been. or are being planned to address this problem, at an organisational level; vulnerability reporting is a key requirement for consumer IoT security in documentation from the ETSI and IEEE, and multiple IoT security organisations. These include the IoT Security Foundation, Alliance for Internet of Things Innovation (AIOTI), Broadband Internet Technical Advisory Group (BITAG), CableLabs, the Internet Society’s Online Trust Alliance, Open Web Application Security Project (OWASP) and hacker collective ‘I am the Cavalry’.