Researchers at Chalmers University of Technology, in Sweden, have unveiled what they described as promising breakthrough for this type of battery, using a catholyte with the help of a graphene sponge.

The researchers’ have developed a porous, sponge-like aerogel, made of reduced graphene oxide, that acts as a free-standing electrode in the battery cell and allows for better and higher utilisation of sulphur.

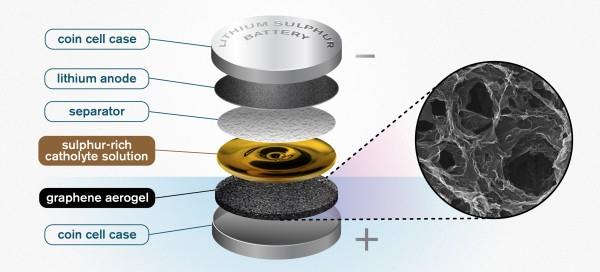

A traditional battery consists of electrodes, an electrolyte and a separator, which acts as a physical barrier, preventing contact between the two electrodes whilst still allowing the transfer of ions.

The researchers initially looked at combining the cathode and electrolyte into one liquid, a so-called ‘catholyte’. The concept can help save weight in the battery, as well as offer faster charging and better power capabilities. Now, with the development of the graphene aerogel, the concept has proved viable, offering some very promising results.

Taking a standard coin cell battery case, the researchers first insert a thin layer of the porous graphene aerogel.

“You take the aerogel, which is a long thin cylinder, and then you slice it – almost like a salami. You take that slice, and compress it, to fit into the battery,” explained Carmen Cavallo of the Department of Physics at Chalmers, and lead researcher on the study.

Then, a sulphur-rich solution – the catholyte – is added to the battery. The highly porous aerogel acts as the support, soaking up the solution like a sponge.

“The porous structure of the graphene aerogel is key. It soaks up a high amount of the catholyte, giving you high enough sulphur loading to make the catholyte concept worthwhile. This kind of semi-liquid catholyte is really essential here. It allows the sulphur to cycle back and forth without any losses. It is not lost through dissolution – because it is already dissolved into the catholyte solution,” says Carmen Cavallo.

Some of the catholyte solution is applied to the separator as well, in order for it to fulfil its electrolyte role. This also maximises the sulphur content of the battery.

Most batteries currently in use are lithium-ion batteries, however it is nearing its limits, so new chemistries are becoming essential for applications with higher power requirements.

Lithium sulphur batteries offer several advantages, including much higher energy density. The best lithium ion batteries currently on the market operate at about 300 watt-hours per kg, with a theoretical maximum of around 350. Lithium sulphur batteries have a theoretical energy density of around 1000 to 1500 watt-hours per kg.

“Furthermore, sulphur is cheap, highly abundant, and much more environmentally friendly. Lithium sulphur batteries also have the advantage of not needing to contain any environmentally harmful fluorine, as is commonly found in lithium ion batteries,” said Aleksandar Matic, Professor at Chalmers Department of Physics, who leads the research group behind the paper.

The problem with lithium sulphur batteries so far has been their instability, and consequent low cycle life. Current versions degenerate fast and have a limited life span with an impractically low number of cycles. But in testing of their new prototype, the Chalmers researchers demonstrated an 85% capacity retention after 350 cycles.

The new design avoids the two main problems with degradation of lithium sulphur batteries – one, that the sulphur dissolves into the electrolyte and is lost, and two, a ‘shuttling effect’, whereby sulphur molecules migrate from the cathode to the anode. In this design, these undesirable issues can be drastically reduced.

The researchers note, however, that there is still a long journey to go before the technology can achieve full market potential. "Since these batteries are produced in an alternative way from most normal batteries, new manufacturing processes will need to be developed to make them commercially viable," said Matic.