The mummy's voice was accurately reproduced as a vowel-like sound based on measurements of the precise dimensions of his extant vocal tract following Computed Tomography (CT) scanning.

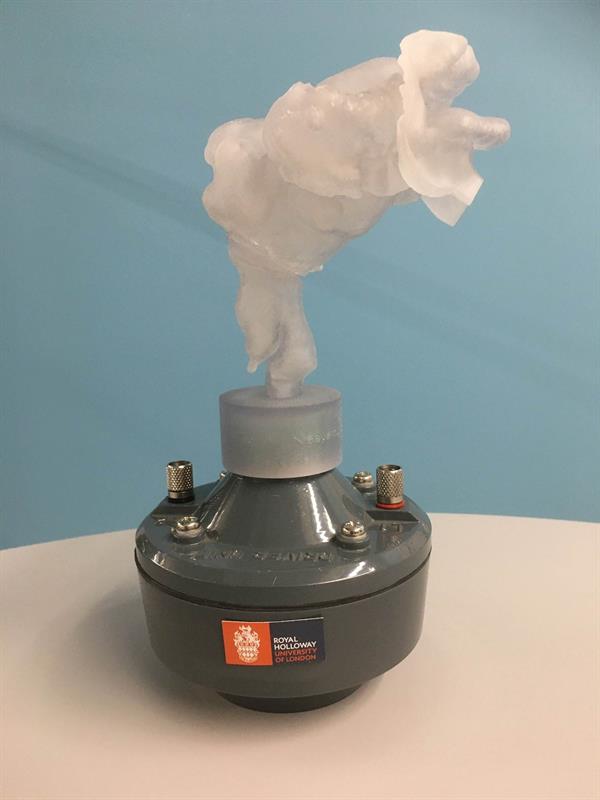

The scan enabled the creation of a 3-D printed vocal tract, known as the Vocal Tract Organ, which was then used to synthesise a vowel sound. The precise dimensions of an individual’s vocal tract makes each of our voices unique, so for the research to work, the soft tissue of the mummy's vocal tract had to be intact.

The mummy, known as Nesyamun, lived during the politically volatile reign of pharaoh Ramses XI (c.1099–1069 BC) over 3,000 years ago, working as a scribe and priest at the state temple of Karnak in Thebes, in modern Luxor. The researchers say his voice was an essential part of his ritual duties which involved spoken as well as sung elements.

Professor David Howard from Royal Holloway, University of London, said, “I was demonstrating the Vocal Tract Organ in June 2013 to colleagues, with implications for providing authentic vocal sounds back to those who have lost the normal speech function of their vocal tract or larynx following an accident or surgery for laryngeal cancer.

“I was then approached by Professor John Schofield who began to think about the archaeological and heritage opportunities of this new development. Hence finding Nesyamun and discovering his vocal tract and soft tissues were in great order for us to be able to do this.

“It has been such an interesting project that has opened a novel window onto the past and we’re very excited to be able to share the sound with people for the first time in 3,000 years.”

Professor Joann Fletcher of the Department of Archaeology at the University of York, added, “While this has wide implications for both healthcare and museum display, its relevance conforms exactly to the ancient Egyptians’ fundamental belief that ‘to speak the name of the dead is to make them live again’.

The research was first published by Nature, and Nesyamun’s remains can be seen in the Ancient Worlds gallery at Leeds City Museum.

Professor David Howard, from the Department of Electronic Engineering at Royal Holloway and Professor John Schofield, Professor Joann Fletcher and Dr Stephen Buckley all from the Department of Archaeology at the University of York, started the project in 2013.