Largely misunderstood by the public and overlooked by governments until a few years ago, the UK’s space industry is an unsung success. Since 2000, turnover has risen by 8.8% a year and, according to a recent study from consultant London Economics, it employs around 37,000 people directly and generates almost £12billion a year.

According to Andy Green, co-chair of Britain’s Space Leadership Council: “The future for Britain’s space industry is not about huge fireworks that cost tons of money; we’re looking at smaller, cheaper investments that will provide real returns.”

The UK has been involved in space since the 1950s – the first official British space programme started in 1952. The first satellite programme started in 1959, with the Ariel series of satellites launched using American rockets. The first British satellite, Ariel 1, was launched in 1962.

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, the UK worked on its own satellite launch capability and a British rocket – Black Arrow – did succeed in placing a British satellite, Prospero, into orbit in the early 1970s before the programme was cancelled as part of government cut-backs.

Britain was also significant in the establishment of the European Space Agency in 1975, with much of its original technology and knowledge derived from UK research programmes.

The Thatcher Government of the 1980s took an axe to the space programmes in which the UK was involved and proceeded to cut investment and support back to the bare minimum. While supporting the science, prestige projects such as manned flight, were deemed unnecessary and uneconomic.

“The Thatcher Government’s view was that space was an expensive hobby; a club through which any UK involvement should be conducted via the European Space Agency,” explains Sir Martin Sweeting, founder and executive chairman of Surrey Satellite Technology (SSTL). “It was a view that tended to prevail until relatively recently.”

A commercial pioneer, SSTL was established in 1985 and became one of the UK’s most successful university spin-outs. Today, it’s part of EADS Astrium, and generating an annual turnover in excess of £130m.

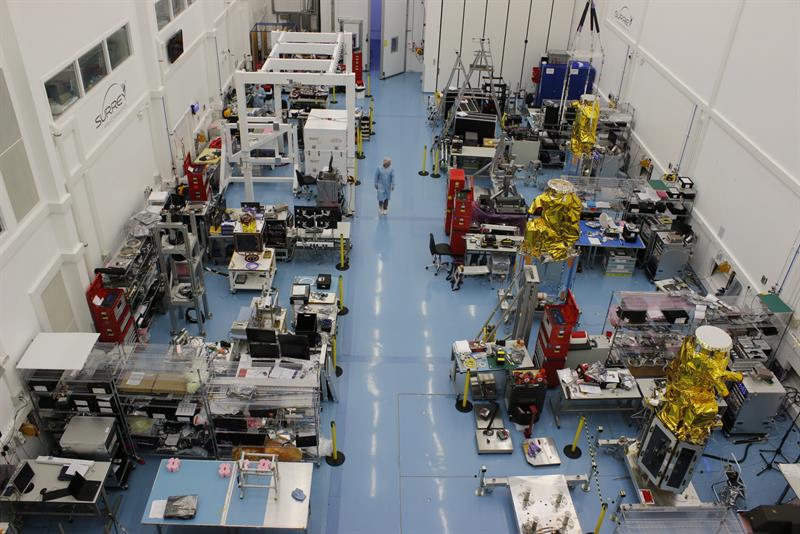

Specialising in the design, manufacture, launch and operation of satellites, it has become a significant competitor in the small or micro satellite market, a sector which accounts for 40% of the global market.

“SSTL has come a long way since our first microsatellites,” Sir Martin said. “Today, small satellites are in demand and I think it is fair to say that, as a company, SSTL played a significant role in creating what is now a global industry. We had to work hard to overcome apathy towards the idea of a UK space industry, as well as a lack of government support. But I believe SSTL is an example of what ambition and innovation in space engineering can ultimately achieve.

“The microelectronics revolution of the 1970s helped change the economics of computing and I believed at the time that it would do the same for space. It provided us with an opportunity to shrink the size of satellites and we pioneered the use of COTS technology to develop small satellites,” he continues. “Until then, satellite equipment tended to be purpose built, was hugely expensive and could take years to build. Often, the technology was itself obsolete when it came to be launched.”

What smaller satellites could offer, according to Sir Martin, was rapid development, quick build times and an ability to fold in new technology more readily.

Profitable from the beginning, SSTL grew organically with Surrey University underwriting its projects. Today, it employs more than 500 staff and assembles satellites and space hardware and operates from state of the art facilities in Guildford.

To date, the company has launched more than 40 satellites, with 20 further spacecraft in manufacture or awaiting launch. There are also 22 payloads for Galileo, Europe’s satellite navigation system.

Under a £110m contract, SSTL is leasing three SSTL-300S1 satellite platforms to Chinese company 21AT. These ‘smallsats’ are designed to provide high resolution imagery and high speed downlink. The three satellites, which will form the DMC3 constellation, incorporate advanced avionics and optical systems, enabling several types of imaging, such as mapping terrain, strip imaging and mosaic imaging for wide areas.

In many respects, SSTL’s success mirrors that of the UK space industry in general.

“It was slow to get off the ground and it was difficult to sell the concept of the ‘small satellite’,” Sir Martin concedes. “Half those we talked to said it was a great idea, the other half said it was lunacy.”

Likewise, UK governments throughout the 1990s tended to view the UK’s space industry as, at best, an interesting niche and, at worst, a costly irrelevance.

However, the economics of space have changed radically in the last 10 years and it is now accepted that space has a crucial role to play in the wider economy.

“Lady Thatcher’s decision to cut funding to the bare minimum probably did us a favour,” suggests Sir Martin. “Rather than relying on state handouts, we were obliged to be commercially focused when it came to deciding what projects we got involved with. As a result, SSTL grew organically and we saw a steady stream of business, the profits from which we used to fund the business.

“But, over time, it became apparent that as the projects on which we worked got bigger – for example, SSTL got involved in Rapid Eye, a project worth tens of millions of pounds – Surrey University wouldn’t be able to act as our lender of last resort; it just didn’t have the funds to underwrite the risks and there was no government funded mechanism to underwrite these types of projects.”

As a result SSTL, spent nearly 10 years looking for a commercial owner and, after several aborted efforts, it found a buyer in the form of EADS (now the Airbus Group).

“To its credit, Surrey University continued to support us over an extended period. We’d looked at venture capitalists and at floating the company, but neither option proved suitable. The focus on short term financial returns was not suited to our business at the time.”

Today, the UK’s space industry is a far more attractive proposition for investors and that is due, in no small part, to the support being provided by government bodies such as Innovate UK and the Space Applications Catapult.

Set up by Innovate UK, Catapults are intended to promote collaboration between scientists, engineers and businesses. In 2012, the then UK Science Minister David Willetts decided to set up the Space Applications Catapult with the aim being to develop new space applications.

Ministers saw space activity as an area where ‘UK plc’ could excel and the Catapult centre in satellite applications looks to provide access to advanced systems for data capture and analysis, supporting the development of new services delivered by satellites.

Throughout the 1990s, the British National Space Centre, set up in 1985, had been at the heart of the UK’s nascent space industry, coordinating different government departments and agencies with interested bodies. It was replaced in 2010 by the UK Space Agency, which now has responsibility for government space policy and key budgets.

As Stuart Martin, CEO of the Space Applications Catapult, explains: ”The Space Agency is there to provide a common view in terms of the UK’s space policy and to ensure that what money is spent on space is spent well.”

Today, the UK’s space industry is worth billions and while the UK may only have a 1.8% share of the global industry’s ‘upstream’ business – the manufacture of space vehicles – it has a disproportionate share of the ‘downstream’ sector, which includes applications, services and data provided by satellites.

According to Martin, the sector’s success and its ability to ‘punch above its weight’ is encouraging entrepreneurs, who had not previously thought of entering the sector to take it seriously.

Oxford Space Systems is a case in point. Set up in 2014, it develops micro satellites using highly flexible composite materials such as carbon fibre. The satellites take only a few weeks to build and cost as little as £30,000. Potential applications are varied but include the delivery of the internet from space and micro high-resolution cameras suitable for the military.

Described as a serial entrepreneur, its chief executive Mike Lawton represents a new wave of innovators working in the UK’s fast growing space industry.

Lawton was one of a number of entrepreneurs who took part in a recent US tour organised by Innovate UK to identify and meet with potential investors and collaborators.

The rise of the small satellite has played to the strengths of the UK space industry.

“Thirty years ago,” said Sir Martin, “the idea of small satellites attracted little attention. Earlier this year, a conference in Liverpool attracted 1700 people representing everything from global businesses to start-ups. Small satellites have moved from being a curiosity to one of the key lanes in what I describe as the space motorway.

“In the last few years, venture capitalists have latched on to the idea of ‘small’ and poured money into start ups; probably more than they’ve needed to. There has been an explosion of propositions.”

According to Lawton, there is a concern that there is ‘too much froth’ at the moment. We need to be careful we don’t turn this into another dotcom bubble. How much of this froth is hype and are these real business opportunities?”

However, Lawton and Sir Martin are optimistic for the future of the UK’s space industry, which is not surprising – just look at the number of companies now operating in the sector. Examples include Arralis Technologies, supplying ultra-fast, radar technology, Bright Ascension, a satellite software specialist, and Gyana, a start-up that is developing machine learning to harness and exploit ‘big data’.

“We have a 80%:20% split between downstream and upstream in the UK,” explains Sir Martin. But while the UK may only account for a small proportion of the global market for space vehicles it has, according to the Catapult’s Martin, an 11.2% share of the operations market and 10.3% of the applications market.

Satellites touch every corner of people’s lives and space, according to both, is all about down to earth applications, whether that is navigation for cars or ships, weather forecasting, satellite broadband or TV broadcasting.

“It is the application of data that the UK does well and when it comes to using space technology, we have some great ideas. The market is moving very quickly, but the UK is well placed and on course to hit the goals it has set itself of creating a £40bn business by 2030,” Sir Martin concludes. However, he warns that ‘continued Government support, from the likes of Innovate UK and Space Applications Catapult, will be crucial’.