Since the 1970s the manufacturing sector in the UK has been portrayed as a sector in decline, and while it may no longer account for a quarter of the UK’s economy, as it did then, the UK remains a leading manufacturing nation - currently the eighth largest in the world.

According to the manufacturer’s organisation, the EEF, manufacturing in the UK as of 2017/18, accounts for 11 per cent of GDP; employs over 2.5million people; and is responsible for 44 per cent of UK exports and 13 per cent of business spend on research and development.

And while the contribution to GDP may have declined, many of the services that once would have been attributed to manufacturing have actually been allocated to different parts of the economy. In fact, if you were to include their contribution, by some accounts, manufacturing’s share of GDP could almost double to 19 per cent.

Whatever the actual figure, manufacturing remains an essential component of the UK economy and a source of skilled labour. It has a big stake in automation, is a significant user and developer of technology and a sizeable investor in R&D, as well as playing an important part in the global economy.

The EEF’s annual conference, held earlier this year, saw the Federation’s new CEO, Stephen Phipson suggest that while manufacturers were facing a challenging political environment, the sector would succeed. But he warned that it would only do so by working together, sharing knowledge and experience.

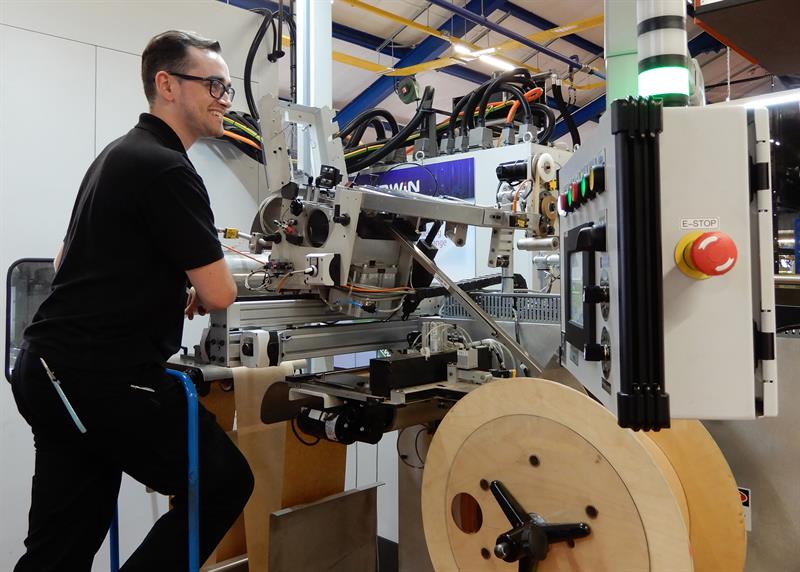

According to Damon de Laszlo, chairman of the Portsmouth-based connector manufacturer Harwin, “Despite what many news reports suggest, manufacturing in the UK is doing remarkably well. The sector is growing and exporting and we are seeing significant levels of investment.”

While de Laszlo paints an upbeat picture he accepts that, “A lot of companies are rattled by the prospect of the unknowable, chief among them Brexit. But so far, there have been few significant problems, and for most businesses, we remain in a ‘wait and see’ pattern.

“None of our programmes are being curtailed or impacted. As with most businesses, we can only do what we can, and our programme for investment, apprenticeships, training and R&D can’t be switched off – we are planning for the long-term.”

De Laszlo highlights a number of the issues that are impacting manufacturers in the UK. Some have been affecting the sector for many years, such as the lack of skills, while others are relatively new.

Among the key ones are: digitalisation, access to labour, training, finance and investment as well as regulation and trade barriers, and the undoubted challenges that will come with leaving the European Union.

Most manufacturers accept that to be successful they will have to deploy advanced – and largely digital – technologies, if they are to compete in an increasingly global marketplace.

The concept of the smart factory is gaining ground and is seen as helping to improve supply chain relationships.

According to Jon Stark, CEO, Peratech, a specialist supplier of force sensing HMI/MMI solutions, “Cloud-based computing, communication, and data-sharing are the foundations upon which we now operate. As a business we wouldn’t be able to compete without these ever-improving IT services.”

However, he warns that, “The sheer volume of business, market and IP intelligence in our industry can be overwhelming. But, by taking the time to focus and articulate clear strategic questions, we are able to source answers, make decisions, and follow through on actions that make positive, sustainable change.”

He makes the point that businesses need to be careful not to waste time collecting intelligence that will not create enterprise value.

“Although, at the same time, sometimes we don’t know what we don’t know, so we have to take risks, and learn fast,” he says.

Technology enables companies to monitor and act upon data derived from machines, people and processes and by delivering real-time data, can highlight weaknesses in systems before they become problems, enabling operators and decision-makers to better manage systems and achieve greater efficiency.

While the case for the adoption of digitalisation is becoming better understood, investment has been less than forthcoming and it is rather the opportunities associated with how technology can help to unlock longer term value, embedded in products – whether that’s through new service offerings, performance monitoring and upgrades – that is drawing the attention of businesses.

Investment is being held back by a lack of confidence in the future, according to the EEF and while most businesses, when asked, suggest that financing is straightforward, very few have said that they found access to finance ‘easy’.

Even if manufacturers do have the cash for investment, many appear reluctant to spend it on technologies and plant that will improve profitability and productivity.

According to de Laszlo, there is too much negativity. “Business sentiment is dominated by uncertainty, which is holding back the investment that industry needs.

“Harwin is a small to medium sized business and I believe that there is a lot of innovation going on in this space. Unlike publicly quoted companies, we’re not having to report to the City every quarter, or explaining why we are spending 10 per cent of our turnover on capital expenditure.”

De Laszlo sits on the EEF’s Economic Policy Committee and says that there are plenty of smaller businesses that, “Understand the need to keep on investing in new technology.

“We’ve been installing computer systems that are able to handle the data generated and required by Industry 4.0. Our entire workforce is being retrained, which will enable Harwin to fully embrace the concept of Industry 4.0, or the smart factory, and increase productivity as a result.”

While it’s difficult to quantify the impact of this move to smarter manufacturing, de Laszlo suggests that installing the right technology will, “Benefit the business across the board. We will be able to integrate point of sale material, which will enable us to undertake better forecasting, which in turn will support improved production planning capabilities.

“By being able to track your systems in real time, instead of deploying theoretical models of output, we will be better able to understand where inefficiencies are. With current systems it’s not possible to capture or process data. We will have real information to do something with.”

| “Cloud-based computing, communication, and data-sharing are the foundations upon which we now operate.” Jon Stark |

Customers of manufacturers face the same challenges of needing to change and improve continually, of upgrading products annually, and of satisfying ever-changing customer demands.

“Our role is to enable that change - better, faster, and cheaper than our competitors can - and to do that, we partner, collaborate, and co-create products directly in the existing supply chain, minimising our customer’s uncertainty of getting a quality product to volume distribution on time,” explains Stark.

“For better or worse, this has been the business model in smartphones for almost a decade. Having started in 2014 with early collaboration, solutions-thinking, and global partnerships, we have modern customer-engagement in our company’s DNA.”

But while the opportunities that advanced digital technology offers are significant, if the education system is unable to produce young people qualified to work with it, then UK manufacturers will struggle.

| Most manufacturers accept that to be successful they have to deploy advanced technologies if they are to compete |

In an interview with the Guardian newspaper, Joe Kaeser, the global chief executive of Siemens, the engineering giant, warned that as the next industrial revolution gets under way, many traditional roles will disappear and that it would become a lot harder to retrain workers whose skills would no longer be relevant.

An obvious solution lies with apprenticeships. But while apprenticeships may finally be seen by many as an alternative to university, the positive view held by manufacturers is being undermined by the fact that many are finding the system extremely difficult to make work for them.

According to de Laszlo managing such schemes and the management of human resources is a massive overhead for smaller businesses.

“We can only afford to do that if we are able to increase our productivity.”

One of the big issues for business is that Government is continually ‘tinkering’ with the education and apprenticeship systems.

“I wish the Government would stop meddling,” de Laszlo says. “If you want enough of the right type of apprenticeships, you need to encourage local colleges to run courses, but every time you change how they are managed or the courses they provide, it throws existing programmes out of kilter.”

One big issue is the confused messaging that has surrounded the Apprenticeship Levy. Few companies have any confidence in the Levy achieving its stated aims, and many have been highly critical of the administrative costs of managing the system.

“But it’s not just issues about the Levy, three local colleges, that we use, were unable to guarantee places for apprentices, because they couldn’t guarantee their budgets.

“The liaison between business and education is difficult, we move at different speeds. The education system is dictated by terms and holidays, which simply don’t apply to industry.

“Industry needs certainty and the messing around with the system that we’ve seen has created massive uncertainty, for a scheme to work and be accepted it requires top management to buy into it and be willing to promote it, and that takes a lot of hard work to deliver.”

Harwin is currently working with Havant & South Downs College to deliver an internationally recognised engineering qualification and to provide students with work experience at the company’s factory in Portsmouth.

“The college approached Harwin, as it wanted a better relationship with industry, and out of our discussions the Harwin Academy was established.”

Twenty students will be starting the full-time course in September this year, and at the end of their first year will be able to apply for a full-time apprenticeship with Harwin, or continue to study full-time at the college.

“The idea is to give them a better understanding of industry and the chance to operate very modern equipment, which they would otherwise not come into contact with.”

De Laszlo says that it’s a “hugely exciting opportunity, but requires real commitment.”

Manufacturers who want to succeed will need to have growth strategies that not only involve getting more efficiency out of their existing processes and investing in new equipment, but will need to be able to find customers to sell to.

Innovation and speed to market will be critical.

| “The liaison between business and education is difficult, we move at different speeds.” Damon de Laszlo |

As Stark explains, “Being a technology solutions company, Peratech must fully embrace the required speed and simplicity of integration far sooner in our research and development lifecycle if we are to catch the mass-commercialisation wave.

“As a newcomer in the force touch business, we entered the market without fully developed reference designs and were forced to invent-to-order. As a result, our competitors were designed into products before we were. We could simply not invent fast enough.”

To address this the company took what Stark describes as a “design-thinking approach” at the earliest stages of technology and product development.

“That meant innovating around established technology applications, our customers’ product development lifecycle, and their existing manufacturing supply chain. As a result, we shortened our time-to-design-win by months.”

However, a growing number of companies are wondering where future profits will come from, according to the EEF, which is disconcerting and could help to explain why overall manufacturing growth has been sluggish.

No review of UK manufacturing can take place without reference to Brexit. Companies like Boeing, Airbus and Jaguar Land Rover have expressed their opinions and raised concerns over the prospect of a hard Brexit.

Manufacturers dislike anything that creates uncertainty, but most seem resigned to the fact that, ‘Brexit is happening,’ so for many, it’s a question of ‘just getting on with it.’

Despite that stoicism, the road to Brexit is certainly proving politically more difficult than anyone expected and what the final deal will look like, and what that will mean for business, remains anyone’s guess.