It remains a cliché of electronics that the connection between design and manufacturing is a brick wall. But that wall is beginning to break down as companies try to streamline production and avoid being stymied by sudden inventory problems and test failures. One big area that is changing is how the design team puts together the bill of materials (BOM) and making purchasing-based decisions much earlier in the process.

“There are a lot of reasons as to why engineers need supply-chain input early on,” says Daniel Fernsebner, product marketing director for PCB products at Cadence Design Systems.

To the designer, a specific manufacturer’s part may look to be an obvious choice based on its datasheet. But an examination of price breaks for different volumes and likely availability may well cause them to select an alternative. Obsolescence remains an ongoing problem.

“The particular component that you are looking to use: its lifecycle status is good today. But tomorrow it’s not. Traditionally, we have had to have purchasing look at what are the buying trends are. If the buying trend is heading downward, it’s often a good indication that it’s not the part you want,” explains Fernsebner.

Leigh Gawne, chief software architect at Altium, says: “Getting lifecycle status information is one of the bigger problems in the industry. The end-of-life notifi cations often don’t make it to the right people. We need a way to get the information where it needs to get.”

In other cases, supplies can simply run dry during production because of sudden inventory shortages with the manufacturing line unable to select an alternative because they do not have the power to make a change even though, for passives and similar multisourced components, other options often exist.

Joe Bohman, senior vice president of lifecycle collaboration software for Siemens Digital Industries Software, says there are clear opportunities to build closer links between contract manufacturing and design following the integration of PCBdesign subsidiary Mentor’s tools with the Teamcenter product-lifecycle management (PLM) software. He claims: “Customers want the contract manufacturers to get right in and make modifi cations in a controlled way.”

Under this new process, the contract manufacturers would, in PLM parlance, ”red-line” parts of the design to replace components with alternatives they believe would be better or simply let them avoid production delays. However, there can be knock-on effects of such course corrections.

Questions around substitutions

Hemant Shah, product management group director for PCB tools at Cadence, points to changes in reliability that might come with a substitution.

“Correlating a change back to design data is an important step: customers are very interested in that. A customer may use one supplier’s part in a batch and order a different one for the next, assuming the equivalent part would not impact the design. But the change could impact the reliability of that product.

“We are seeing customers asking to have the real-time ability to bring that information back into a change and analyse it.”

EDA vendors have taken the first steps to closing the circle with manufacturing by building links to live supply-chain data into the PCB schematics-capture and layout tools.

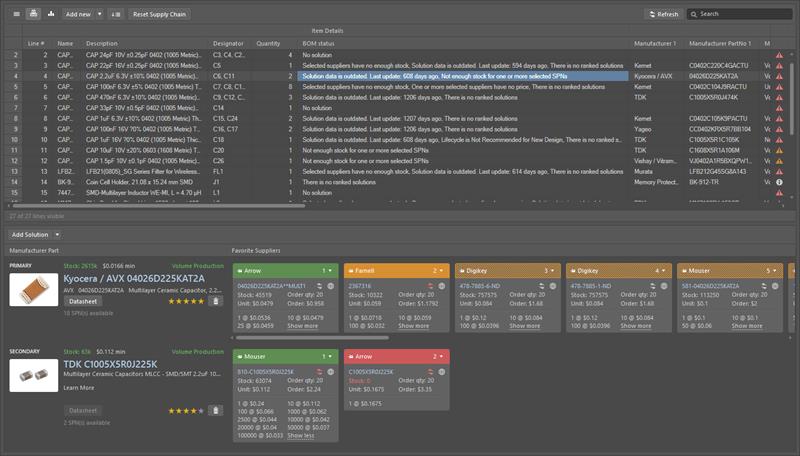

The ActiveBOM facility in Altium 365, launched at the beginning of the year, has a three-tier model for each component instance. The CAD component has symbol and footprint.

“All we care about with his is the design intent,” says Gawne. “There could be many manufacturer parts that meets those specifi cations. The physical part we call the manufacturer component. It’s a one-to-many relationship that allows us within ActiveBOM to have secondary and tertiary parts where multisourcing is possible. You can rank them: it could be lowest cost or the one that’s most widely available, or let the EMS decide which one. The third type is the supplier component, which represents the supply chain: where can I go to get that manufacturer part?”

Cadence is using an approach it calls BOM validation in the Pulse platform that it has built into the latest releases of its PCB tools. This checks the availability of components the design team has picked. One issue with live supply-chain data is that it changes rapidly, says Fernsebner. The company is looking to incorporate ways to model supply-chain patterns. “Making a better choice off of predictive analytics is where we’re going with Pulse.”

Similarly, Altium sees the use of historical data as being a useful guide to availability over the course of a product’s lifecycle. “That’s not in the system right now but it’s something that will come.”

Designers could head off supply problems through the use of defensive planning.

Below: Altium’s ActiveBOM facility 365 provides a three-tier model for each component instance.

“When searching for a part you could type in a part number or do a faceted search, based on case type, tolerance and other factors. If you end up choosing something with specific characteristics and only get one or two results that implies there aren’t too many of those parts around,” says Gawne. Subtle changes to a filter circuit that allows for a different tolerance band could open up more possibilities that loosens the constraints on the supply chain.

The EDA vendors see the process data that comes back from manufacturing as becoming a bigger influence on design. As with supply-chain intelligence, the issue is one of information flow. “That kind of thing is coming back informally through a phone call or email. But does it make it back to the designer? We will see an improvement in that formal feedback,” says Gawne.

Dan Hoz, general manager of Mentor’s Valor division, says he sees the potential to take this manufacturing data back to design. The design-for-manufacturing (DFM) analysis that some companies already use to minimise the impact of things like solder-paste issues will help, often by respecting keep-out zones and overlaps to account for variations.

Hoz, however, sees further optimisations in the way in which manufacturing can influence design. The orientation and neighbourhood around a component may influence the failure rate and this information will appear during inspection and test. This information is today being used to tune the assembly processes.

Manufacturing analysis can highlight components that are more prone to failure during assembly than others. Hoz points to the problem he sees frequently where the way in which boards move around the shop floor can cause problems.

“You have the issue of sensitive components: there are components that can only survive for a few hours outside but we find them sitting on the line for days.”

Subtle changes to the PCB layout may be able to reduce that wastage further. The problem may be the choice of component or it may be one that can be addressed by changing the layout of the board to make it easier to mount the more sensitive devices later in the process or by taking the step of moving to a different facility if the reason why the boards are getting held up is due to bottlenecks forming.

Hoz says the use of a digital-twin approach for storing data about board designs and production outcomes will help reduce waste.

“Using the metrics we can go back to the design and run some course corrections,” he says, adding that the software is not ready yet but it is something the company is working on. The feedback may, ultimately, go back to component manufacturers if it turns out materials choices lead to unexpected failures after assembly.

After decades of living apart, design and manufacturing are gradually getting to know each other better.