You might not think there was the need for too many variants, yet search the websites of leading distributors for 'op amp' and you'll find thousands of parts. There is, apparently, quite a lot of life left in the old dog that is the op amp.

The op amp dates back to the early 1940s, according to some sources. But it was only in the late 1960s that it adopted its current form factor, with the development of monolithic process technology. And some of today's products have no trouble in tracing their heritage back to those early days.

Michael Arkin, strategic marketing manager for Analog Devices' linear products and technology group, noted the recently launched ADA4177 could trace its lineage way back. "Analog Devices bought Precision Monolithics in 1990. PMI was founded in the late 1960s and developed a reputation for some of the best op amps, including the OP07. This still does well each year and is a workhorse," he claimed. "The ADA4177 and 4077 families can be regarded as the fourth and fifth generations of the OP07."

Analog Devices is one of a host of companies supplying op amps. Amongst the others is ON Semiconductor and Diodes, which acquired BCD Semiconductor in March 2013; a move which it admitted 'greatly increased' its analogue portfolio by adding standard linear and power management products.

When you talk with companies such as these, there is an acceptance that cost is an important parameter. All contend there's more to op amps than simply selling them for as little as possible. But Simon Ramsdale, Diode's European strategic marketing manager, said: "There's always the issue of trying to make devices more cheaply. We ask ourselves how we can shrink die size and take advantage of our manufacturing capability. With devices such as these, it's often about cost, so designers are looking to companies like Diodes to take industry standard devices and support them at the price the market is looking for."

Arkin noted: "While performance matters, cost is very important. The mainstream is getting more competitive but, at the low end, prices are probably at the bottom, so it comes down to manufacturing efficiency."

Aditya Jain manages the development of On Semiconductor's op amps and comparators. He explained the typical application for an op amp. "They're used when an external analogue signal needs to be boosted. All sensors produce a very small voltage – sometimes microVolts – and this signal needs to be digitised. But the A/D converter in an MCU is likely to have a full scale of 5V and that won't work if you're feeding it microVolts – and that's where the op amp comes in."

Jain said that some precision op amps work with sensors that produce very small outputs. "If you look at non precision op amps, they might have an input offset of something like 8mV. If the sensor produces microVolts, you're losing the signal because of error."

There is a range of issues which op amp developers are looking to address: one is that of precision. "Companies have, over the years, always achieved precision," Jain asserted, "but the devices still drifted with temperature and time. In the latest precision devices, there is zero drift; these parts not only have low input offset voltage, but also cancelling offset architectures."

Arkin pointed to three ways in which op amp technology is advancing. One is greater precision, better thermal drift and better long term drift. "Thermal drift is a key data sheet spec," he accepted. "Five years ago, offset was a primary spec, but customers are now looking at thermal performance. These are definitely areas in which efforts are being made. In general, we are pushing closer to ideal performance levels."

Arkin also pointed to speed and noise. "Applications need higher bandwidth and that's linked to speed. Noise and bandwidth integrate to reduce the signal to noise ratio, as well as affecting power consumption."

Jain said many precision op amps now have input offsets as low as 50µV. "Some are as low as 10nV," he added. "On Semi is trying to address those markets that require precision with new parts; we're not looking at competing with older precision devices."

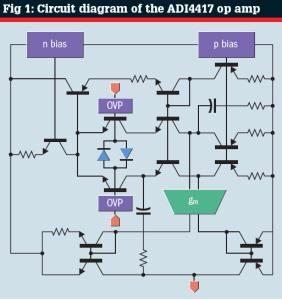

On Semi's precision devices use a chopping architecture; these sample the input offset error and cancel it continually. "Typically, op amps like these run at around 350kHz, but the cancelling offset aspect may run at something like 100kHz."

Arkin said chopping speeds are increasing. "It used to be done at a few kHz," he noted, "but now it can be as high as 700kHz."

Ramsdale said one of the latest op amps from Diodes – the TLC271 – is a second source of a TI design. "It's available in single, dual and quad versions, but the single version is programmable, with the design enabling three bias modes – high, medium and micro power. Previously, users have tend to select high or micro bias power, where they need speed for signal processing or want to save power because it's a battery powered app. But which option is selected depends on the load being driven – even in micro power mode, some designers want to drive higher loads."

Jain picked up the power theme. "If op amps are going into battery powered devices, designers don't want them to burn current. And they need to support 1.8V operation in such apps."

Traditionally, he said, op amps have run from a 2.7V supply. "But On Semi has a process which can go to 1.8V. Five years ago, we didn't have a 1.8V device; now, there is growing demand."

Arkin agreed. "We didn't do this in the past, but customers are now building devices powered by a couple of coin cells and need 1.8V parts. Our question is now 'should we do more?'."

But supply voltages are also increasing. Arkin said Analog's CMOS parts used to be specified for 5V operation. "They moved to 16 and 18V and, if you look at the market, most companies have 30V CMOS parts. This means they are poised to replace bipolar and JFET based devices because performance is good enough and there are other benefits."

Jain added: "At the low end, they'll support 1.8 to 5.5V but, for some apps, they could have a 10V or 12V supply, as well as ±15V or ±18V."

All three contributors agreed that rail to rail operation is also growing in importance.

Concluding, Arkin said Analog was fighting hard to change perceptions about op amps. "They aren't the 'same old thing'. It's the things that can be done with them that have changed."