The interest generated by Handel-C saw the software commercialised by Embedded Solutions, later to become Celoxica. Handel-C, meanwhile, was bought and sold and is now part of Mentor Graphics’ DK Design Suite. Mentor says this software, which supports code being compiled directly into FPGA logic, is suitable for those using C and C++, but who don’t have much hardware design experience.

While efforts have been made to develop C to hardware technologies, there has also been work on developing C to multicore systems, recognising the growing importance of the latter technology in embedded systems.

One of the biggest European projects to date is bringing together something like 100 partners to work on the challenge. Called EMC² – ‘Embedded Multi-Core systems for Mixed Criticality applications in dynamic and changeable real-time environments’ – the ARTEMIS Joint Undertaking project has a budget of some €100million.

Flemming Christensen, managing director of Sundance Multiprocessor Technology, said: “EMC² is massive and one of the EU’s biggest funded projects.”

According to Christensen, EMC² ‘wants to make an impact’. “It’s addressing areas such as embedded computing, the IoT and the things that go around them. The focus is on multicore and on time critical applications, where things cannot go wrong.” And the EMC² website highlights this, noting ‘the objective of EMC² is to establish multicore technology in all relevant embedded systems domains’.

According to EMC², the development of multicore hardware architectures and concepts with partial reconfiguration will open up what it calls a ‘new era’ of time multiplexed hardware coprocessors. These devices, which are expected to reduce power consumption and improve efficiency, have the potential to enable reconfigurable multicore processors, it contends.

“EMC² is also about making multicore systems safe,” Christensen noted, “because these types of device will eventually be used in embedded computing. In short, it’s about making sequential applications into multicore applications.”

He estimated that some 95% of embedded solutions feature a single CPU, but pointed out that almost all new processors are multicore. In a complex system, such as a car, there might be more than 100 CPUs. “Wouldn’t it be better if fewer multicore chips could be used?” he wondered. And that multicore device might not just feature CPU cores. “EMC²’s goal is ‘generic’ multicore; it could be a number of CPUs, with hardware accelerators alongside,” he continued. “So while the C to VHDL aspect of EMC²’s work is relevant to FPGA users, there is also a significant element that is exploring how to map software to multiple CPUs.”

In Christensen’s opinion, this latter aspect remains the ‘Holy Grail’ of embedded software development. “It might be 20 years before the multicore dilemma is solved, maybe longer.”

Sundance has a long history of developing C to VHDL hardware and software and has a range of products for high performance embedded processing applications. Initially, it designed devices for the parallel processing market, but has since broadened its scope to include PC add-in boards and modules. Most of its products are based on TI’s TMS320C6x processors or on Xilinx’ Virtex FPGAs.

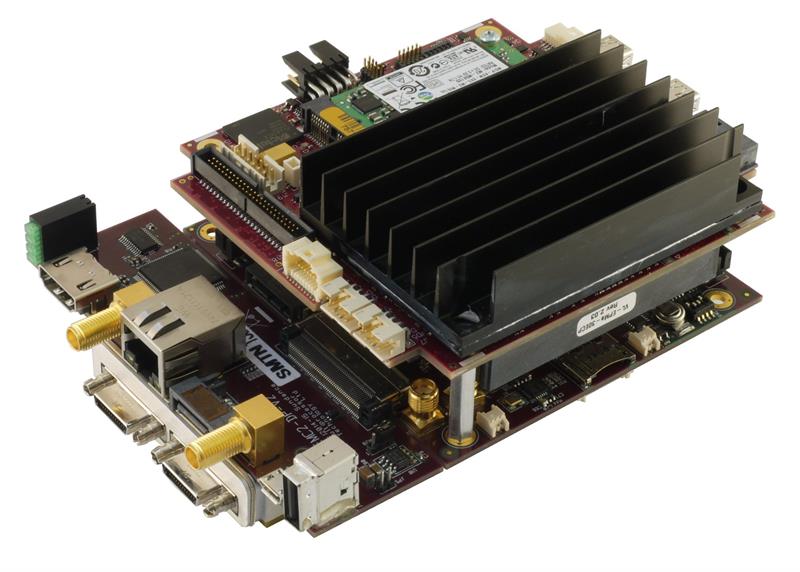

A Versalogic single board computer fitted with an EMC-KU35 and a dual camera link

Sundance is also a member of HiPEAC, the European Network on High Performance and Embedded Architecture and Compilation. The organisation’s mission is to steer and increase European research in high performance and embedded computing systems and to stimulate cooperation academia and industry.

“HiPEAC has been trying to get Europe involved in multiprocessing,” Christensen noted. “It promotes high end projects and, although it’s separate from EMC² and mainly academic, it is trying to help all projects to have a greater commercial element.”

Sundance has been proposing a design and development platform which is modular and scalable. “We’ve now done that,” Christensen said. “The platform is scalable; you can ‘hook up’ as many boards as you want using PCI-Express as the backbone.”

Because the platform which Sundance has developed is based on a Xilinx Zynq device, the concept of C to VHDL can be broadened to encompass C to FPGA, bringing the potential of reconfigurable hardware. And a recent Xilinx development – SDSoC – has made this task easier.

Christensen said industry’s efforts to develop C to VHDL have been underway for many years, pointing to Handel-C as one of the earliest developments.

“But the problem then was all the available tools required one engineer to sit alongside another couple of engineers and it could take three people or more to produce an application,” said Christensen.

In the early 1990s, Sundance co-developed a board called HARP-2 that combined a 32bit Inmos Transputer with a Xilinx XC3195 FPGA. The board, supported by Handel-C, was commercialised by Celoxica.

“Although the Transputer was easy to program, one of the problems with this solution, and hence its limited adoption,” Christensen recalled, “was the cost of the necessary software licences and the requirement for detailed FPGA/VHDL knowledge.

“Xilinx realised this and developed SDSoC, targeted at Zynq devices,” he continued, adding “SDSoC can be used by any experienced C programmer.”

Christensen pointed out that SDSoC allows developers to take C code, run it on an ARM core and work out how fast it runs. “Not all C code can be adapted to run in parallel, but the SDSoC environment will help with the evaluation, not only providing an idea of how much quicker the code might run, but also the cost of the power and logic required.”

At a recent HiPEAC meeting, researchers from the Czech Institute of Information Theory and Automation (UTIA) demonstrated video processing algorithms running on Sundance’s EMC² platform and the SDSoC design environment.

“The main innovation is in the SDSoC design framework,” said Jiří Kadlec, head of UTIA’s signal processing department. “Developers can now estimate the acceleration for their algorithms, explore different avenues and export the best solutions as a standalone C application or Linux user space application.”

The demonstration used Sundance’s Zynq based EMC² board to execute standalone C application programs and to initialise and synchronise the hardware accelerated video processing chain.

According to the team, the demonstrations were found to enable up to eight times faster edge detection and 50 times faster motion detection without a significant increase in power consumption.

Christensen added: “UTIA took a C routine and converted it into an IP core for an FPGA, then instantiated it multiple times in a Zynq processor.

This represents a step forward for embedded applications where edge and/or motion detection is important, such as those relating to security, medical uses, unmanned vehicles and image processing in general.

“It can take hours for software tools to produce a hardware version, but you can now do it in C and it takes very little time to compile and test. It shows what is possible if you take the same code and run multiple versions; you get something like a parallel processor,” he concluded.