Today, aeroplanes are joined in the skies by unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), or drones. Although UAVs are used in industrial and commercial applications, a military UAV is defined as 20kg or more. They are also classified according to altitude range, with high altitude, long endurance (HALE) and medium altitude, long endurance (MALE) versions. There are also unmanned combat aerial vehicles (UCAVs).

Military UAVs are the largest segment of the UAV market, ahead of industrial, agricultural and commercial uses. They are used for intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) or equipped to carry missiles in combat operations which are deemed too dangerous if a human pilot should be shot down, lost or captured. UAVs can be remotely operated, semi-, or full-autonomously, using either passive or active sensors, such as light detection and ranging (Lidar) cameras and an on-board embedded computer for the computer vision and path planning algorithms.

The principles of SWaP

The amount of data and computing, as well as the need for agility, places a burden on UAV design and adds another dimension to the size, weight and power (SWaP) principle.

Minimising size, weight and optimising power has been a long-held tenet of mil/high-rel design. Today, mission times have also been extended, further fuelling the need for optimal density in constrained or limited areas.

In addition to the need to minimise component count and reduce wiring, processors for processing vision imaging and data transmission to and from multiple sensors must be power-efficient, secure and reliable.

Mil-spec modules

One response to the SWaP criteria has been from Acromag, which has developed mezzanine modules that boost I/O density. Its AcroPack I/O modules are for use with the company’s AcroPack carrier cards for CompactPCI Serial, Mini-ITX Com Express Type 10, PCIe, XMC or VPX-based systems. They enable developers to route I/O through a carrier card without any loose cabling, using a 100-pin connector that is positioned face-down on the module. The AcroPack modules measure 30 x 70mm and can up to four can be plugged into a single carrier card.

The latest additions to the range include the AP513, an isolated RS232 communications module based on the PCI Express mini card (mPCIe) standard and the APCe7043, a ¾ length PCIe carrier card for smaller computers and servers.

The AP513 has four RS232 serial ports, each isolated to 250V from digital circuitry and from the three other ports to protect equipment and signal integrity in electrically noisy environments. For data processing, each port has 256-byte FIFO buffers on the transmit and receive lines to minimise CPU operation.

SWaP restrictions can mean a full length module cannot be used. In response, the company has introduced the APCe7043 (pictured). This 10 inches long module carrier card, based on mPCIe, has expansion slots for up to four I/O modules to install analogue or digital I/O, serial comms, FPGA, Mil-Std-1553 or CAN bus for example. Two slots have sockets for optional, isolated power supplies to support isolated I/O modules.

All modules run on Linux, Windows or VxWorks OS.

Another company, Abaco, believes the SWaP maxim is no longer sufficient for high-rel design. It has introduced SWaP-C3, adding cost, cooling and compliance to the embedded board design checklist.

As defence budgets have dwindled, cost is now considered to be as much an evaluation point as the conventional size, weight and power.

Lorne Graves, chief technology officer, Abaco Systems explains: “In most cases, there is a cost associated with [mil-aero] design. Companies are not building 10s or 100s of thousands . . . to build 200, 500, there is a cost,” he says. The company’s solution is to use a group of products to accelerate commercial off the shelf (COTS) development. Evaluations need to take into account the lifetime cost of ownership. If a product is easy to upgrade to meet new levels of functionality, this lowers the lifetime.

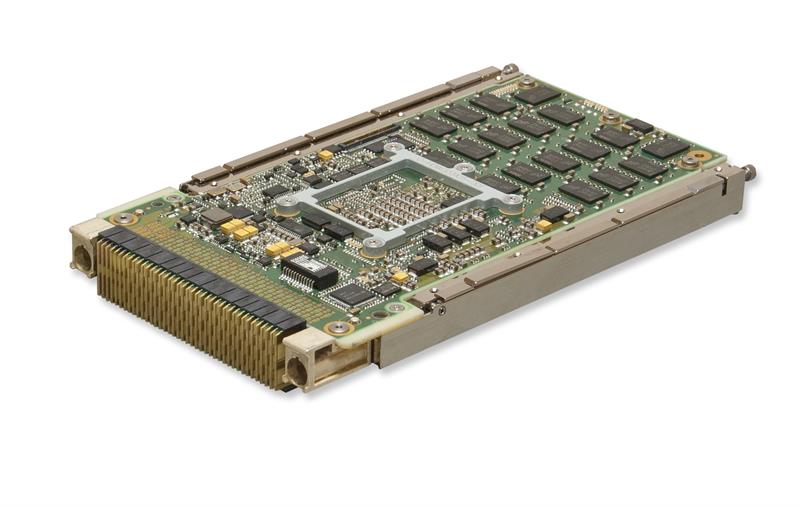

Above: Cooling technology in the SBC347D enables HPEC performance up to 750C

Cooling design

Processor manufacturers are working hard to optimise power efficiency, but still, high performance embedded computing (HPEC) systems generate heat which can jeopardise performance.

Abaco’s HPEC SBC347D SBC, for example, uses the Intel Xeon D multi-core processor in a low power SoC and operates at its full core speed at temperatures up to 75°C. The predictable performance meets mission-critical scenarios that require real time determinism and its 20 PCIe lanes can be used with the company’s general purpose graphics processing unit (GPGPU) modules.

The use of traditional cooling techniques such as fins, fans and heat sinks, add to both weight and size. To counter this, Abaco uses integrated heat pipes in heat assemblies to improve the thermal design power (TDP). “Cooling is more than just adding heat sinks,” says Graves. He advocates efficient cooling via design techniques, for example removing heat more efficiently through the heat plates, to the assembly and then out to the platform. As a result, a system can run at the same frequency but lower operating temperatures and without having to reduce the processor performance at high temperatures.

“Cooling is most impactful on the performance of video for a UAV,” reveals Graves. Vision systems also rely on edge computing which typically demands the highest, most SWaP-critical design. These systems also need computing power at the edge for a faster response and for more communication at the edge for faster reaction times to avoid collisions. “The reaction time for collision avoidance in ground-based autonomous vehicles moving at 30mph has to be scaled up for applications operating at 200mph,” observes Graves.

The differences in performance for mil-aero embedded computing, for example operating at altitude and for a period of 10 years or more, accounts for the third C, compliance. “Abaco uses the same technology as commercial applications, but we make sure they are rugged enough for operation in extremes of temperature, conditions and altitude,” explains Graves.

The life cycle of a vehicle is around 10 to 40 years, he says. He cites the B52 platform which has been in service since Vietnam and which is still being upgraded for new equipment. “Compare this with 10 to 15 years in the commercial arena,” says Graves. “In 2008, the iPhone was introduced, today we have the iPhone X (10)”.

The asymmetric progress of mil-aerospace and commerce highlights the issue of compliance. The mil-aero market is now demanding the same type of processing power as we have in cell phones, desktops servers and cloud computing, says Graves. They are also, however, tasked with additional parameters, namely operating at altitudes, temperatures and reliability levels far beyond anything in a phone or server.

Abaco uses the same technology as its commercial applications, says Graves, but makes sure embedded boards are rugged for use at altitude, saltwater and explosive resistant and operate in high temperatures.

“We are trying to move at the same pace as commercial products; ruggedising existing products and looking to new ones,” concludes Graves.