We were treated to a dazzling and sophisticated light show: more than 17,000 bracelets winked multiple colours, turned on and off by seating section, and flashed to the beat of thumping music. It was a thrilling example of how much fun could be had with wearable electronics.

After we left the arena, we noticed that our bracelets’ LEDs would flash whenever we moved our arms. A motion sensor! I was eager to take the bracelet apart to discover which company’s MEMS sensor might be inside.

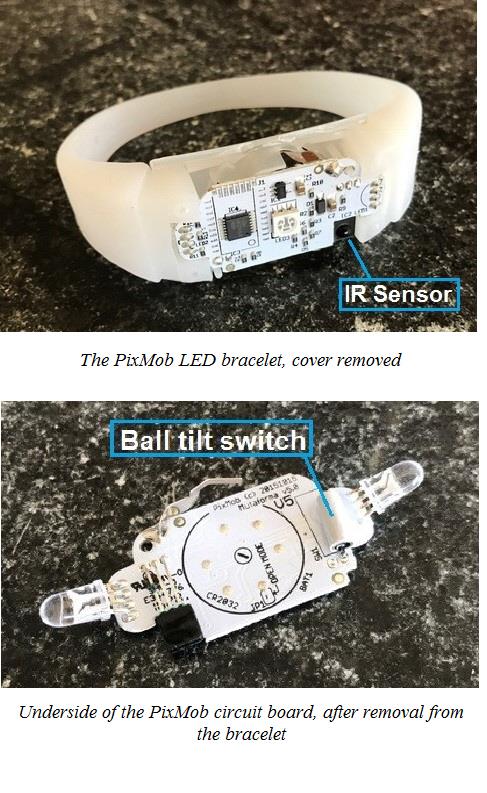

When I extracted the circuit board from the bracelet, I turned it over a few times, seeking the MEMS chip. I identified an ABOV MCU, an EEPROM, a bunch of discretes and an infrared sensor (for communications) – but no MEMS chip.

I placed the board under a stereo microscope for closer inspection. To my great surprise, I discovered that what I had initially thought to be an electrolytic capacitor was actually a ball tilt switch motion sensor. Unbelievable!

My goodness; this networked, wearable electronic device was using a 1920s-era motion sensor*. A ball tilt switch is nothing more than a metal ball in a tube that rolls when tilted or moved, shorting two electrical leads within the tube. The Rolamite sensor, a slightly more complex version of the ball tilt switch, was used to deploy airbags in cars until MEMS accelerometers came along in the 1990s.

The PixMob engineers had clearly done their jobs well. The board’s design indicated they had deliberately engineered the bracelet for ‘good enough’ performance at bare minimum cost. Their discipline extended to selecting a Century-old mechanical sensor for this most modern of products.

There’s a lesson here for all MEMS business people who aspire to sell sensors for cost-conscious or disposable products – the cheapest ‘good enough’ and simplest sensor will win the socket, not the smallest, nor the most accurate, nor the most sophisticated.

MEMS may seem like the obvious choice for wearable electronics, but this time it got beaten by an old mechanical sensor.

*The oldest patent I could find after a quick search. If you know of an older one, please let me know.

Author:

Dr Alissa Fitzgerald is founder of MEMS product development specialist AM Fitzgerald & Associates

This is an edited version of an article originally published in the AMFitzgerald newsletter and is used with permission.